In a long running matrimonial dispute the court in Etemadi v Maali 2021 BCSC 1003 refused to order the defendant to produce her computer hard drive to her husband.

A computer hard drive is not a document, as contemplated by the provisions of Rule 9-1 Rule 1(1) of the Supreme Court Family Rules.

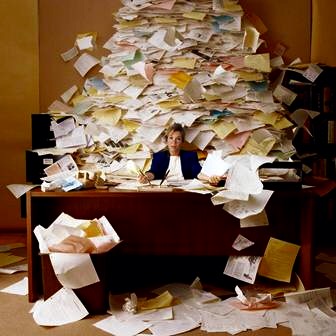

Rather, a hard drive is the digital equivalent of a bookshelf, a filing cabinet or a documentary repository. While the court may order the production of relevant documents stored in a hard drive, the Rules do not authorize an unrestricted search of a digital storage device.

A “document” is defined in Rule. 1(1) of the Supreme Court Family Rules as having an extended meaning ,”…and includes a photograph, film, recording of sound any record of a permanent or semi-permanent character and any information recorded or stored by means of any device”.

The court was influenced by the decision o of Desgagne v. Yuen, 2006 BCSC 955 where the court found the defendants were seeking disclosure, from the computer, of all available documentation to recording virtually every element of the plaintiff’s activities for all of her waking hours- an extremely broad ” fishing expedition”.

No specific documents from the computer had been sought and the court found that the claimant wished to leaf through the digital files on the hard drive to determine whether any relevant material has been disclosed, and that is not a mode of disclosure contemplated by the Supreme Court Family Rules.

Etemedi v Maali referred to the decision of the British Columbia Court of Appeal in Privest Properties Ltd. v. W.R. Grace & Co. – Conn (1992), 74 B.C.L.R. (2d) 353 (C.A.).

In that case, the plaintiff sought access to a document repository established by the defence (for use in U.S. litigation due to jurisdictional overlap). After reviewing the provisions of then Rule 26, Southin, JA, commented, at paras. 37-40:

“But these rules do not empower a judge to require a party to give access to his opponent to documents which are neither in his list not in an affidavit required to be made under sub-rule 4 nor referred to in one of the documents listed in sub-rule 8.

Sub-rule 10 confers no power to make the order under appeal which is really an authorization to search.

If the court had power to make this order then it would also have the power to permit a litigant access to all places in which his opponent might keep documents to see if there is anything “relating to any matter in question”.

It would require much different rules to give the court such an extraordinary invasive power in circumstances such as these. However, if the fact that the respondents at one time wrongly believed to exist – that is to say, a deliberate concealment of documents – was proven to exist, it may be that an order of the sort made here could be made for the purpose of redressing dishonesty in the litigtion.

In the case of Mossey v. Argue, 2013 BCSC 2078, Master Young, as she then was, reviewed the provisions of the Supreme Court Family Rules with respect to document disclosure, and then went on to say as follows:

The law is not that a party can demand every document that has come into a party’s possession or control because they are suspicious of wrongdoing. They have to specify what document or class of documents they are requesting and tie it to an issue in the proceedings.

As Master Baker said in Anderson v. Kauhane (February 22, 2011), Vancouver Registry — and this is quoted in Master Bouck’s decision in Przybysz (as read in):

…there is a higher duty on a party requesting documents under…Rule 7-1(11)…they must satisfy either the party being demanded or the court…with an explanation “with reasonable specificity that indicates the reason why such additional documents or classes of documents should be disclosed”…

Przybysz and Anderson are civil cases, but civil Rule 7-1(8) and Supreme Court Family Rule 9-1(8) are identical. The only difference in document disclosure in family law proceedings is that the first tier of disclosure is at least partially proscribed in the family law financial disclosure Rule 5-1, which makes disclosure of income information from personal and corporate sources mandatory and sets out some basic rules for disclosure of business interests. There will likely be other documents that fit into the first tier of disclosure.

However, gone are the days of the full underwear drawer disclosure, unless the demand is made with specificity and justification.

In this case, the initial demand letter does not set out the reason for the demand. I have combed through the letters and emails to see if that flaw has been addressed. Some of the follow-up emails and letters do allude to some specific issues that the respondent wishes to prove. The notice of application is a disappointing cut-and-paste of the original deficient demand letter. It does not specify many of the documents or classes of documents, and it does not establish a reason for many of the requests.

The rules of document disclosure were changed to avoid document disclosure demands like the one I have before me today. It is impractical to expect a party conducting business will be required to produce a photocopy of every cheque front and back, every invoice, credit and debit note, and receipts for years of business transactions. The costs of the legal proceeding will far exceed the value received by the party if the court has to condone forensic audits of the parties’ businesses because the parties are mistrustful of one another.

Mistrust is a common theme in matrimonial proceedings. The threshold for document disclosure has to be higher than that.

.