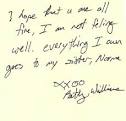

A week prior to the testator’s death she gave the executor his will and a signed but unwitnessed document entitled “codicil to my last will” (codicil) for safe keeping, telling executor she thought codicil was valid.

The Executor recognized her handwriting including signatures to be the testator’s handwriting.

The Executor brought an application for determination of whether handwritten alterations to the will and codicil represented the testator’s testamentary intentions and the application was granted.

The court held that the codicil represented the testator’s testamentary intentions .

The recognition by the executor of her handwriting and signatures as the testator’s, the fact that testator gave document to executor week before her death, use of wording “codicil to my last will” and “to be read out by my lawyer,” and reference to reading of will, all suggested document was deliberate or fixed and final expression of testator’s intention to dispose of property upon her death .

The Testator’s expression in the codicil as to how her daughter would use gift of property did not create trust, but was expression of wishes or recommendations and unenforceable, but the $10,000 gift to her grandson was a deliberate expression of the testator’s wish and testamentary intention, and that portion of the codicil was fully effective, as though made as part of the will . The statement in the codicil referencing the use of the residue did not vary the explicit residue clause in will.

15 Section 58 of the WESA has been considered in one British Columbia Supreme Court case, a decision of Madam Justice Dickson (Young Estate, Re, 2015 BCSC 182 (B.C. S.C.)). In Young, Madam Justice Dickson notes the absence of any British Columbia authority in interpreting this new section and she looks to other provinces’ legislation. She notes that s. 58 of the WESA is most like the curative provisions in s. 23 of Manitoba’s Wills Act, The Wills Act, C.C.S.M. c. W150.

16 After reviewing Manitoba’s authorities, Madam Justice Dickson concluded that the curative power is intensely fact-sensitive. The first threshold issue is whether the document is authentic. The core issue is whether the non-compliant document represents the deceased’s testamentary intention. That concept was explained in the Manitoba Court of Appeal decision George v. Daily (1997), 143 D.L.R. (4th) 273 (Man. C.A.). In that decision, Philp J.A. explained the limits placed on the court’s curative powers. At paragraphs 62 and 65 he stated:

62 Not every expression made by a person, whether made orally or in writing, respecting the disposition of his/her property on death embodies his/her testamentary intentions. …

65 The term “testamentary intention” means much more than a person’s expression of how he would like his/her property to be disposed of after death. The essential quality of the term is that there must be a deliberate or fixed and final expression of intention as to the disposal of his/her property on death: …

17 Justice Dickson explained that the intention must be fixed and final at the material time, which will vary depending on the circumstances, but does not have to be irrevocable intention given that a Will is revocable until the death of the testator. She concluded, at paragraphs 36 and 37:

[36] The burden of proof that a non-compliant document embodies the deceased’s testamentary intentions is a balance of probabilities. A wide range of factors may be relevant to establishing their existence in a particular case. Although context specific, these factors may include the presence of the deceased’s signature, the deceased’s handwriting, witness signatures, revocation of previous wills, funeral arrangements, specific bequests and the title of the document: Sawatzky at para. 21; Kuszak at para. 7; Martineau at para. 21.

[37] While imperfect or even non-compliance with formal testamentary requirements may be overcome by application of a sufficiently broad curative provision, the further a document departs from the formal requirements the harder it may be for the court to find it embodies the deceased’s testamentary intention: George at para. 81.