Estate disputes frequently involve issues relating to who is the true beneficial owner of a property due to a myriad of fact patterns, and the legal arguments invariably refer to the presumption of legal and beneficial ownership of indefeasible title.

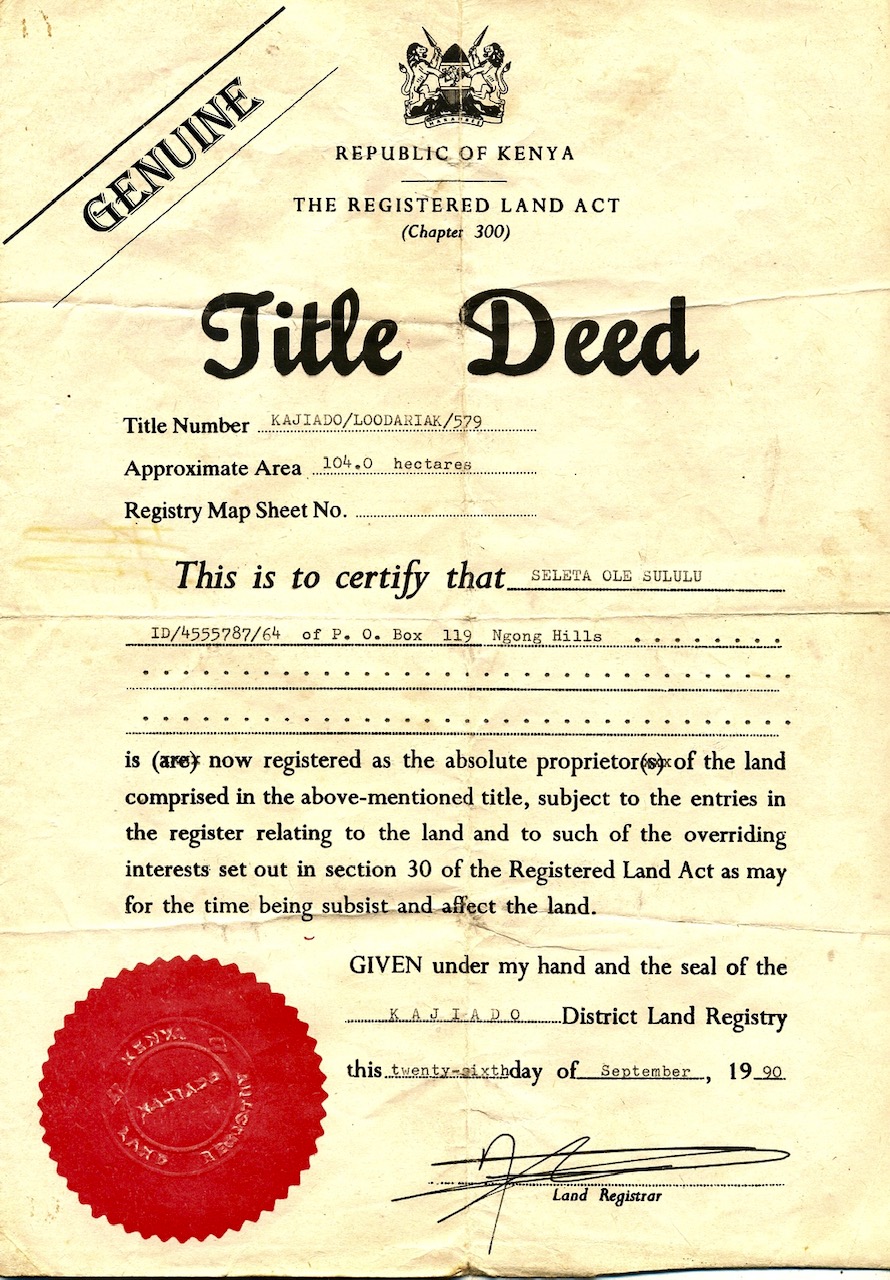

The first thing any lawyer will do in any dispute as to the legal vs beneficial ownership of a parcel of property is to conduct a land title search.

British Columbia uses the Torrens property regime, and section 23(2) Land title Act creates a statutory presumption that the registered owner on title is presumed to be the legal and beneficial owner of the property.

Fellowship Deaconry Association of BC v Fellowship Deaconry Inc. 2019 BCSC 1476 dealt with a dispute of “ownership” – the plaintiff Church asserting that the defendant held the property in trust for the Church . The defendant relied inter alia on the presumption of S. 23(2) Land Title Act, that the defendant as registered owner was the presumed legal and beneficial owner of the property.

Like any presumption in law, contrary evidence will often overcome the presumption, and the same section 23(2) of the Land Title act provides three options in which the presumption may be rebutted:

1) The operation of a resulting trust, which may be inferred where no value is given for a legal interest;

2) the operation of an agreement between the parties that is contrary to the registered legal title;

3) taking into account the underlying equitable interests between the parties ( for example, a claim such as unjust enrichment)

Most estate disputes involve the law of resulting trust, and while the Deaconry case did review the law of resulting trusts, it ultimately decided the case on the basis of the parties intention based on a review of correspondence and conduct prior to and at the time of the purchase of the property.

In the Deaconry decision , the court ultimately decided it did not have to result to the presumption of resulting trust, as the court found after a review of the evidence and correspondence, that the defendant did not intend to retain a beneficial interest in the church, and that legal title was transferred to the defendant until some agreement about repayment had been reached or fulfilled. The court found that this was the mutual intention of both parties that both the time of the purchase and when title was transferred in 1971.

The court specifically found that the evidence was sufficient to establish the three certainties necessary to create a trust, namely :

1) certainty of intention,

2) certainty of the object of the trust,

3) certainty of subject matter of the trust.

With respect to the law relating to the three certainties necessary to create a trust, the court referred to Norman Estate v . Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Canada, 2014 BCCA 277 at paragraph 35.