In C.C. v. S.P.R., 2022 BCSC 1057 [C.C.], the court considered the admissibility of surreptitious recordings. During the trial, the respondent who had made the recordings sought to adduce them, along with transcripts, into evidence. The court . noted (at para. 4) that while the practice of secretly recording a party for use in a family law proceeding should be discouraged, “there are circumstances where the probative value of admitting surreptitiously made recording outweighs the prejudicial effect of its admission”.

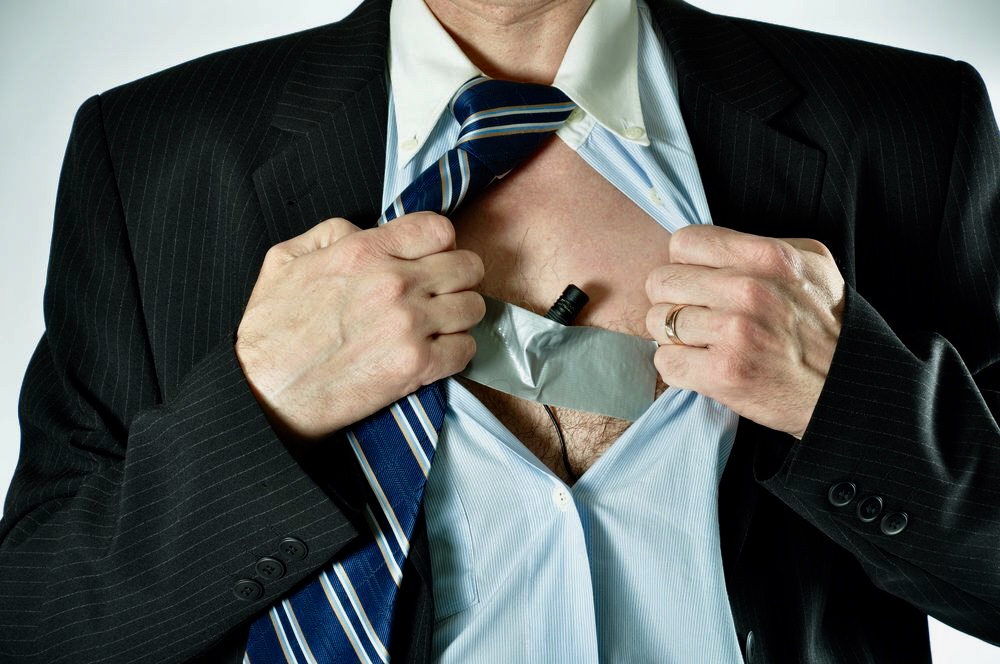

Note that it is a criminal offence to secretly record a conversation that is between third parties that you are not privy to the conversation , it is not illegal to record a conversations that you are a party to.

In C.C., at paras. 31-32, Gibb-Carsley J. set out the test applicable in British Columbia for determining the admissibility of surreptitious recordings:

[31] In British Columbia, the court has developed a four-part test to determine the admissibility of surreptitious recordings.

This test as set out by Justice Skolrood in Finch v. Finch, 2014 BCSC 653 at para. 62 [Finch] can be summarized as follows:

i. the recordings must be relevant;

ii. the participants must be accurately identified;

iii. the recordings must be trustworthy; and

iv. the court must be satisfied that the probative value of the recordings outweighs its prejudicial effects.

The court considered the leading cases in this province regarding the use of surreptitious recordings including A.D.B. v. E.B., [1997] B.C.J. No. 227, 1997 CarswellBC 104 (S.C.), Sweeten v. Sweeten, [1996] B.C.J. No. 3138, 1996 CanLII 2972 (S.C.) [Sweeten], and Mathews v. Mathews, 2007 BCSC 1825 [Mathews], and accepted that as a starting point there is a limited discretion for the court to exclude the evidence simply on a policy basis.