One of the difficulties in advising clients in wills variation cases is that under the WESA provisions relating to the variance of wills, the trial judge has an absolute discretion in his or her award, if any, under the act. The five panel appeal decision of Kish v Doyle and Sobchak 2016 BCCA 65 dealt with the wills variation court action of two parties who met late in life, had children from previous marriages and did not wish to be treated as spouses.

In the course of their judgment, they examined the fine line between the exercise of judicial discretion and the finding of facts , as well as the standard of review to the exercise should judicial discretion on appeal.

Exercise of Discretion

[33] The line between the exercise of judicial discretion and the finding of facts is not easy to enunciate. For purposes of this case, I respectfully adopt Lord Bingham’s description of judicial discretion given in The Business of Judging: Selected Essays and Speeches (2000):

According to my definition, an issue falls within a judge’s discretion if, being governed by no rule of law, its resolution depends on the individual judge’s assessment (within such boundaries as have been laid down) of what it is fair and just to do in the particular case. He has no discretion in making his findings of fact. He has no discretion in his rulings on the law. But when, having made any necessary finding of fact and necessary ruling of law, he has to choose between different courses of action, orders, penalties or remedies he then exercises a discretion. It is only when he reaches the stage of asking himself what is the fair and just thing to do or order in the instant case that embarks on the exercise of a discretion.

I believe this definition to be broadly consistent with the usage adopted in statutes. [At 36; emphasis added.]

Lord Bingham also explains that fact-finding is not “discretionary”, although some judges have described it as such. In his words:

… it is one thing to say that the responsibility of finding the facts is entrusted to a particular person or body, be he judge, arbitrator, official or public authority, and that such finding is to be treated as conclusive or virtually so. But it is quite another to describe that function as discretionary. It is, I suggest, nothing of the kind. In finding the facts the judge’s job is to consider all the conflicting evidence this wav and that and decide as best he can where the truth lies. It is very much the task performed, for instance, by the historian or the journalist as part of his stock in trade. The judges of course are constricted by formalities and rules of evidence which do not afflict them.

On the other hand, he has powers of compelling testimony which they would envy. It is none the less essentially the same function. Yet to say of a historian or journalist that he exercised a discretion in reaching conclusions of fact would, I suggest, be regarded as a libellous. The judge must exercise judgment, not discretion, in finding the facts, and it is usually the most difficult and often most exacting task which the civil trial judge has to undertake. [At 37; emphasis added.]

[34] The standard of review applicable in Canada to the exercise of judicial discretion is found in Friends of the Oldman River Society v. Canada (Minister of Transport) [1992] 1 S.C.R. 3. There La Forest J. wrote for the majority:

Stone J.A. cited Polylok Corp. v. Montreal Fast Print (1975) Ltd., [1984] 1 F.C. 713 (C.A.), which in turn approved of the following statement of Viscount Simon L.C. in Charies Osenton & Co. v. Johnston, [1942] A.C. 130, at p. 138:

The law as to the reversal by a court of appeal of an order made by the judge below in the exercise his discretion is well-established, and difficulty that arises is due only to the application of well-settled principles in an individual case. The appellate tribunal is not at liberty merely to substitute its own exercise of discretion for the discretion already exercised by the judge. In other words, appellate authorities ought not to reverse the order merely because they would themselves have exercised the original discretion, had it attached to them, in a different way. But if the appellate tribunal reaches the clear conclusion that there has been a wrongful exercise of discretion in that no weight, or no sufficient weight, has been given to relevant considerations such as those urged before us bv the appellant, then the reversal of the order on appeal may be justified.

That was essentially the standard adopted by this Court in Harelkin v. University of Regina, [1979] 2 S.C.R. 561, where Beetz J. said, at p. 588:

Second, in declining to evaluate, difficult as it may have been, whether or not the failure to render natural justice could be cured in the appeal, the learned trial judge refused to take into consideration a major element for the determination of the case, thereby failing to exercise his discretion on relevant grounds and giving no choice to the Court of Appeal but to intervene. [At 76-7; emphasis by underlining added.]

This standard was affirmed and supplemented more recently in Penner v. Niagara (Regional Police Services Board) 2013 SCC 19, where the Court stated:

A discretionary decision of a lower court will be reversible where that court misdirected itself or came to a decision that is so clearly wrong that it amounts to an injustice:

Elsom v. Elsom, [1989] 1 S.C.R. 1367, at p. 1375. Reversing a lower court’s discretionary decision is also appropriate where the lower court gives no or insufficient weight to relevant considerations: Friends of the Oldman River Society v. Canada …

[At para. 27.]

Eberwein Estate v. Saleem

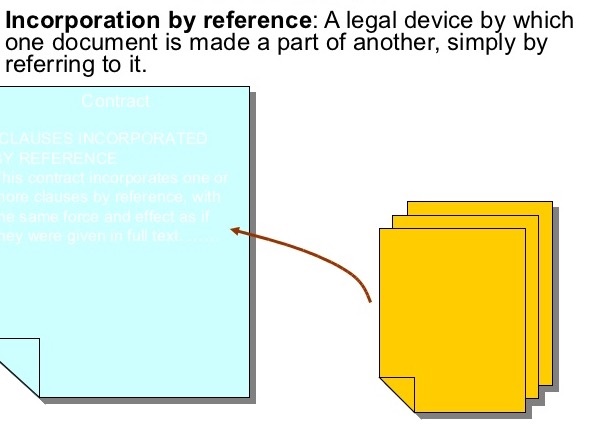

Eberwein Estate v. Saleem Incorporation by reference typically occurs when a trust company is appointed executor and the deceased’s will makes reference to a certain fee agreement entered into between the then client and the trust company to retain their services as executor/trustee and to pay a fee schedule.

Incorporation by reference typically occurs when a trust company is appointed executor and the deceased’s will makes reference to a certain fee agreement entered into between the then client and the trust company to retain their services as executor/trustee and to pay a fee schedule. People, including heirs, go missing for all sorts of reasons all the time. This of course presents a problem to an executor who must serve all heirs under the will, and anyone who would inherit on an intestacy, along with a copy of any application for probate with a copy of the will attached.

People, including heirs, go missing for all sorts of reasons all the time. This of course presents a problem to an executor who must serve all heirs under the will, and anyone who would inherit on an intestacy, along with a copy of any application for probate with a copy of the will attached.

Pet Trusts

Pet Trusts