Pleadings are important. They delineate the issues between the parties and inform the opposing party of the nature of the case they have to meet. Pleadings prevent surprises at trial and limit the issues to be tried.

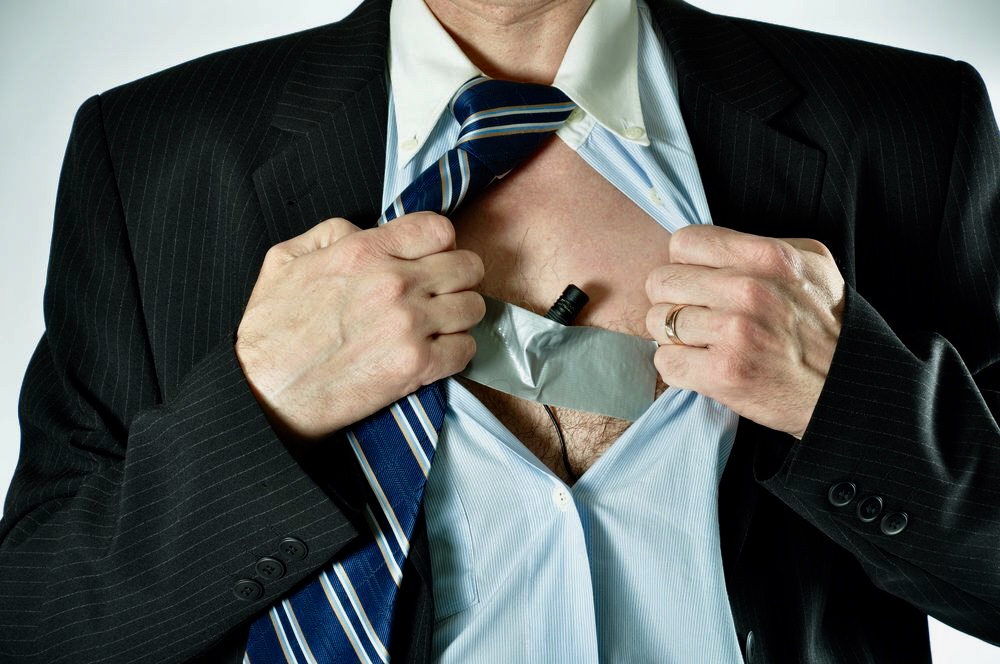

Parties must plead the legal basis for seeking relief.

Rule 3-1 of the Supreme Court Civil Rules [Rules] addresses what is properly contained in an originating pleading:

Contents of notice of civil claim

(2) A notice of civil claim must do the following:

(a) set out a concise statement of the material facts giving rise to the claim;

(b) set out the relief sought by the plaintiff against each named defendant;

(c) set out a concise summary of the legal basis for the relief sought;

(d) set out the proposed place of trial;

(e) if the plaintiff sues or a defendant is sued in a representative capacity, show in what capacity the plaintiff sues or the defendant is being sued;

(f) provide the date collection information required in the appendix to the form;

(g) otherwise comply with Rule 3-7.

Rule 3-7(18) addresses particulars:

If the party pleading relies on misrepresentation, fraud, breach of trust, wilful default or undue influence, or if particulars may be necessary, full particulars, with dates and items if applicable, must be stated in the pleading.

Rule 3-7(12) addresses pleadings subsequent to a notice of civil claim:

In a pleading subsequent to a notice of civil claim, a party must plead specifically any matter of fact or point of law that

(a) the party alleges makes a claim or defence of the opposite party not maintainable;

(b) if not specifically pleaded, might take the other party by surprise, or

(c) raises issues of fact not arising out of the preceding pleading.

Rule 6-1(8) provides that amendments to pleadings may be granted at trial. Unless otherwise ordered by the court, “if an amendment is granted during a trial or hearing, an order need not be taken out and the amended pleading need not be filed or served.”

There are numerous cases which discuss the purpose and importance of the Rules with respect to pleadings.

In Sahyoun v. Ho, 2013 BCSC 1143, Justice Voith, as he then was, discussed the function of pleadings generally:

[16] The new Rules alter the structure in which pleadings are to be prepared. The core object of a notice of civil claim, however, remains the same. That object is concisely captured in Frederick M. Irvine, ed., McLachlin and Taylor, British Columbia Practice, 3rd ed.; vol. 1 (Markham, Ont.: LexisNexis Canada Inc., 2006 at 3-4 – 3-4.1:

If a statement of claim (or, under the current Rules, a notice of civil claim) is to serve the ultimate function of pleadings, namely, the clear definition of the issues of fact and law to be determined by the court, the material facts of each cause of action relied upon should be stated with certainty and precision, and in their naturel order, so as to disclose the three elements essential to every cause of action, namely, the plaintiff’s right or title; the defendant’s wrongful act violating that right or title; and the consequent damage, whether nominal or substantial. The material facts should be stated succinctly and the particulars should follow and should be identified as such…

[17] These requirements serve two foundational purposes: efficiency and fairness. These purposes align with Rule 1-3 which confirms that “the object of [the] Supreme Court rules is to secure the just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every proceeding on its merits.”

[18] I emphasize efficiency because a proper notice of civil claim enables a defendant to identify the claim he or she must address and meet. The response filed by a defendant, together with the notice of civil claim and further particulars, if any, will confine the ambit of examinations for discovery and of the issues addressed at the trial itself. Proper pleadings limit the prospect of delay or adjournments. They allow parties to focus their resources on those matters that are of import and to ignore those that are not. They facilitate effective case management and the role of the trier of fact.

[19] A proper notice of civil claim also advances the fairness of pre-trial processes and of the trial. Defendants should not be required to divine the claim(s) being made against them. They should not have to guess what it is they are alleged to have done.

…

There are cases which specifically discuss the importance of pleading fraud and misrepresentation. Some disallow claims under those headings where they were not pleaded in accordance with Rule 3-7(18): Karimi v. Gu, 2016 BCSC 1060, at paras. 183-187.

In Grewal v. Sandhu, 2012 BCCA 26, at para. 19, the Court of Appeal held that “[a]n allegation of fraud must be scrupulously pleaded and fully particularized.” In Grewal, the Court held that the plaintiff could not seek to establish a case of fraud against the defendant that depended entirely on the defendant’s husband’s knowledge since there was no pleaded allegation that the husband was a participant in a fraud.

In Terrim Properties Ltd. v. Sorprop Holdings Ltd., 2012 BCSC 985, the plaintiff framed its argument in negligence but had not pleaded it. Justice Melnick held that the negligence claim could not be maintained since the plaintiff had not pleaded negligence. Justice Melnick said the following:

[17] …It is trite law (as well as R. 3-1(2)(c)) that one must plead the legal basis for seeking relief. Neither counsel for the defendants came to court prepared to deal with a claim for negligence. They anticipated, properly, that they were here to meet a claim in nuisance.

[…]

[19] Given the above, it is not necessary for me to come to any conclusions respecting the capacity of Terrim to maintain all of the claims it advances…

Applying a different approach in Berthin v. Berthin, 2018 BCCA 57, the Court of Appeal left open the principle that a pleading need not explicitly say “equitable fraud”:

[22] With great respect, I am of the view that the judge erred in dismissing the fraud claim on the basis that it disclosed no reasonable cause of action. The judge fell into error because he assessed the pleading against the requisite elements of the tort of civil fraud, rather than equitable fraud relied on by Mr. Berthin. The error occurred no doubt in part because the notice of civil claim unhelpfully failed to use the phrase “equitable fraud”. However, counsel for Mr. Berthin made submissions at the hearing based on equitable fraud and in my view the facts and averments pleaded are capable of supporting that cause of action.

In Anenda Systems Inc. v. AL13 Systems Inc., 2020 BCSC 2077 [Anenda], Justice Lyster considered circumstances where, contrary to Rule 3-7(18), the defendant had not provided full particulars of the fraud in which it alleged the plaintiff had engaged. Justice Lyster found that the defendant should have pleaded equitable fraud and granted leave to file a notice of civil claim rather than further amend its counterclaim.

In Whiten v. Pilot Insurance Co., 2002 SCC 18, the defendant argued that the statement of claim did not plead the factual basis for an independent actionable wrong. The statement of claim did include a claim for punitive and exemplary damages. Justice Binnie, at paras. 89 to 90, stated “if the respondent was in any doubt about the facts giving rise to the claim, it ought to have applied for particulars and, in my opinion, it would have been entitled to them.” Justice Binnie noted there was no surprise except as to the quantum of punitive damages. He further noted that the plaintiff had pleaded a breach of the duty to deal fairly and in good faith in handling the plaintiff’s claim.

In Cook v. Neufeld, 2022 BCSC 6:

The general rule is that amendments to pleadings should be permitted as necessary to allow the real issues between the parties to be determined. Although more stringent considerations apply when amendments are sought at the end of trial, provided the proposed amendments would not cause injustice, unfairness or prejudice to the non-amending party, the amendments are generally allowed so that the real issues between the parties can be adjudicated upon: Argo Ventures Inc. v. Choi, 2019 BCSC 86 at paras. 6, 8 and 9; Lam v. Chiu, 2012 BCSC 677 at para. 10.