Many estate disputes arise out of alleged “broken promises” to be provided for after death in a certain agreed manner concerning real property in the estate of the deceased that were relied and acted upon by the disappointed beneficiary. Such a claim arises under the equitable law of proprietary estoppel.

A “classic” example of proprietary estoppel occurred in Linde v Linde 2019 BCSC 1586 where the parents promised to provide the family farm in their estates to a son who worked the farm for fifty years for little or no wages and restricted his career paths based on repeated assurances and expectations that he would inherit the farm on his parent’s death.

The court set aside a transfer of the land to a third party after a falling out with the son based on the equitable principles of proprietary estoppel.The law was further clarified by the decision of Cowper-Smith v Morgan 2017 SCC 61, that many of those broken promises that were relied upon may be legally enforceable through the law of proprietary estoppel.

The Broken Promise: Facts

The facts of the leading proprietary estoppel case Cowper-Smith v Morgan are interesting and perhaps even “common”. The promise made by the sister and relied upon by her brother is a scenario that might very well be reasonably agreed upon between siblings.

An elderly mother had three children: two adult sons, N and M, and an adult daughter, G.

In 2001, the mother made a Declaration of Trust, transferring her house and other assets into her own and the daughters names in joint tenancy, and made a will naming her executrix, trustee and beneficiary of half of estate, with balance to the sons “ if the daughter saw fit”.

In 2007, son M moved from England to look after their mother on his sister’s assurance that she would sell him her one-third interest in the house.

M looked after his mother until her death in 2010.

The sister took no steps to divide the estate as per the promise made by her to her brother who cared for their mother for three years, so he brought a successful court action in the Supreme Court of Canada that granted orders declaring that the daughter held the mother’s home and investments in trust for the estate and that brother M was entitled to purchase her one-third interest in the home, and for an order distributing the home and investments in accordance with the mother’s 2002 will.

The trial judge held that M acted to his detriment in moving from England to look after his mother, relying on his sister’s agreement to his conditions for the move, and that, in doing so, M acted reasonably. The Trial judge also held that the brother’s right to purchase the daughter’s one-third interest in house was the minimum required to satisfy equity.

The Supreme Court of Canada agreed with the trial judge, finding inter alia that reasonableness is circumstantial, and it would be out of step with equity’s purpose to make a hard rule that reliance on a promise by party with no present interest in property can never be reasonable.

Of legal note, the daughter did not own any interest in the estate at the time of the brother’s reliance yet this was not barrier to success of proprietary estoppel claim . As soon as the daughter received interest in property, promissory estoppel attached.

The principles that can be derived from Cowper-Smith are:

An equity arises when:

1) A representation or assurance is made to the claimant, on the basis of which the claimant expects that he will enjoy some right or benefit over property;

2) The claimant relies on that expectation by doing or refraining from doing something, and his or her reliance is reasonable in all the circumstances;

3) The claimant suffers a detriment as a result of his reasonable reliance, such that it would be unfair or unjust for the party responsible for the representation or assurance to go back on his or her word.

The representation or assurance may be express or implied. An equity that is under crystallized arises at the time of detrimental reliance on a representation or assurance.

When the party responsible for the representation or assurance possesses an interest in the property sufficient to fulfill the claimant’s expectation, proprietary estoppel may give effect to the equity by making the representation or assurance binding.

The Remedy

Where a claimant has established proprietary estoppel, the court has considerable discretion in crafting a remedy that suits the circumstances.

The claimant who establishes the need for proprietary estoppel is entitled only to the minimum relief necessary to satisfy the equity in his favor, and cannot obtain more than he expected.

There must be a proportionality between the expectation and the detriment. Estoppel claims concern promises which, since they are unsupported by consideration, are initially revocable.

Other Fact Situations

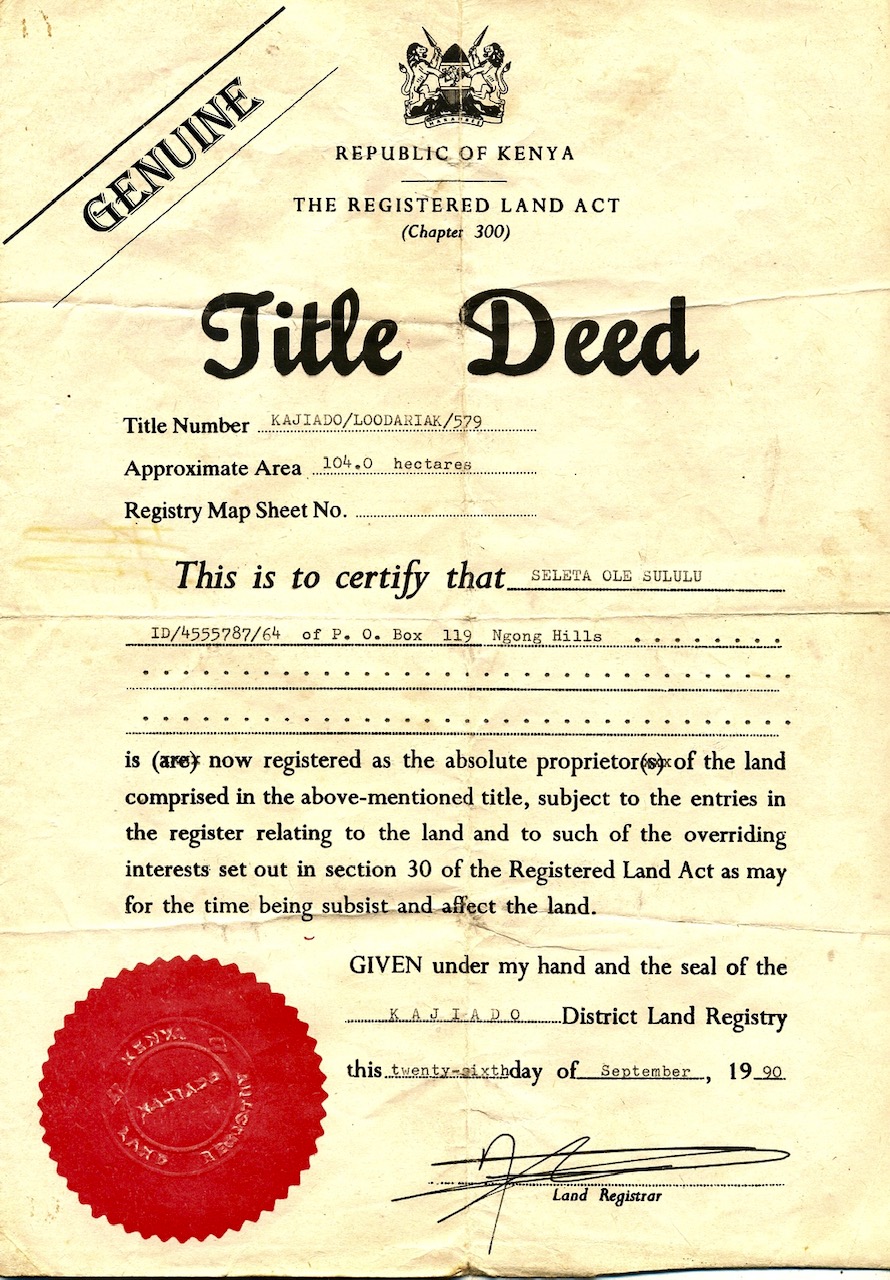

Proprietary estoppel claims need not be limited in their application to estate claims-there is a myriad of factual situations related to real property where promises are made and a person acts on the promises to his or her detriment. Equity arises to enforce the agreement through the application of promissory estoppel.

A claim for promissory estoppel was rejected in Burge v Emmonds Estate 2017 BCSC 2437. The dispute was the interpretation of a mediation agreement and whether it created an easement.

The Court in Burge stated:

The principles of promissory estoppel are well settled. The petitioners must establish that the respondents have, by words or conduct, made a promise or assurance which was intended to affect their legal relationship and to be acted on. Furthermore, the petitioners must establish that, in reliance on the representation, they acted on it or in some way changed their position: Maracle para. 13.

76 In order to prove proprietary estoppel, the petitioners must prove four things:

(1) that the claim is brought in a property context;

(2) that the respondents made a representation to the petitioners that an easement would be granted;

(3) that the petitioners reasonably relied on that representation; and

(4) that it would be unconscionable and unjust in all the circumstances for the respondents to go back on the assumption they allowed the petitioners to make:

The claimant must demonstrate why it would be unconscionable or unfair for the other party to be allowed to rely on and enforce its legal rights. In that regard, then, it would “rarely, if ever, be unconscionable to insist on strict legal rights” in the absence of any detriment or prejudice to the claimant: Thus, the claimant typically must demonstrate that it will suffer some detriment if the other party is allowed to rely on its strict legal rights.

Conclusion

Not all promises made by a testator to provide for a claimant are enforceable. as they must relate to real property.

It is the promisee’s detrimental reliance on the promise which makes it irrevocable. Once that occurs there is simply no question of the promisor changing his or her mind.

The detriment need not consist of expenditure of money or other quantifiable financial detriment, so long as it is something substantial.