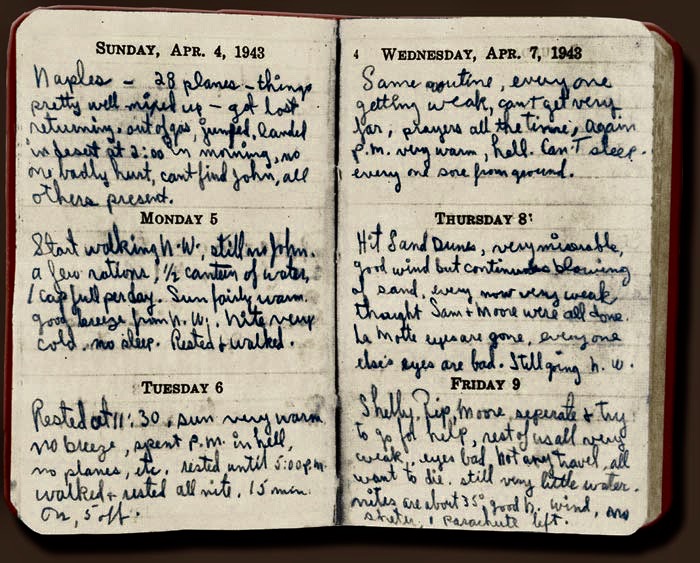

Re Hadley Estate 2017 BCCA 311 was upheld by the Court of appeal in finding that a rambling journal was not a will that could be “cured” by S 58 WESA.

This was the first appeal court decision on Section 58 WESA.

Section 58 of the WESA

[33] British Columbia was a “strict compliance” jurisdiction prior to passage of the WESA. Under s. 4 of the Wills Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 489, testators were obliged to comply strictly with execution and attestation formalities for creating a will for it to be valid. The same was true for revoking, altering or reviving a will: Wills Act, ss. 14, 17, 18. These formal requirements sometimes led to a will-maker’s testamentary intentions being defeated for no good reason. As a result, the British Columbia Law Institute recommended the introduction of a dispensing power to relieve against the consequences of non-compliance with testamentary formalities as part of a general reform of wills and estate administration law: BCLI, Wills, Estates and Succession: A Modern Legal Framework (BCLI Report No. 45, June 2006) at xiv.

[34] Section 58 of the WESA is the legislative response to the BCLI recommendation. Remedial in nature, it confers a broad discretion on the court to order that a “record or document or writing or marking on a will or document” be fully effective, despite non-compliance with the statutory requirements. Although s. 58 cannot be used to uphold a will that is substantively invalid, it permits the court to cure issues of formal invalidity in prescribed circumstances:

Court order curing deficiencies

58 (1) In this section, “record” includes data that

(a) is recorded or stored electronically,

(b) can be read by a person, and

(c) is capable of reproduction in a visible form.

(2) On application, the court may make an order under subsection (3) if the court determines that a record, document or writing or marking on a will or document represents

(a) the testamentary intentions of a deceased person,

(b) the intention of a deceased person to revoke, alter or revive a will or testamentary disposition of the deceased person, or

(c) the intention of a deceased person to revoke, alter or revive a testamentary disposition contained in a document other than a will.

(3) Even though the making, revocation, alteration or revival of a will does not comply with this Act, the court may, as the circumstances require, order that a record or document or writing or marking on a will or document be fully effective as though it had been made

(a) as the will or part of the will of the deceased person,

(b) as a revocation, alteration or revival of a will of the deceased person, or

(c) as the testamentary intention of the deceased person.

…

[35] For an order to be granted under s. 58 of the WESA, the court must be satisfied that a document represents the testamentary intentions of the deceased person. However, unlike the curative provisions in some provinces, s. 58 does not require a minimum level of execution or other formality for a testamentary document to be found fully effective. Regardless of its form, if the court grants an order under s. 58(3), the document may be admitted to probate.

[36] As discussed in Estate of Young, s. 58 is very similar to Manitoba’s curative provision and thus the leading appellate authority on its meaning is George v. Daily. George and several other Manitoba authorities are reviewed in Estate of Young, which review need not be repeated. Their import is summarized at paras. 34–37:

[34] As is apparent from the foregoing, a determination of whether to exercise the court’s curative power with respect to a non-compliant document is inevitably and intensely fact-sensitive. Two principal issues for consideration emerge from the post-1995 Manitoba authorities. The first in an obvious threshold issue: is the document authentic? The second, and core, issue is whether the non-compliant document represents the deceased’s testamentary intentions, as that concept was explained in George.

[35] In George the court confirmed that testamentary intention means much more than the expression of how a person would like his or her property to be disposed of after death. The key question is whether the document records a deliberate or fixed and final expression of intention as to the disposal of the deceased’s property on death. A deliberate or fixed and final intention is not the equivalent of an irrevocable intention, given that a will, by its nature, is revocable until the death of its maker. Rather, the intention must be fixed and final at the material time, which will vary depending on the circumstances.

[36] The burden of proof that a non-compliant document embodies the deceased’s testamentary intentions is a balance of probabilities. A wide range of factors may be relevant to establishing their existence in a particular case. Although context specific, these factors may include the presence of the deceased’s signature, the deceased’s handwriting, witness signatures, revocation of previous wills, funeral arrangements, specific bequests and the title of the document: Sawatzky at para. 21; Kuszak at para. 7; Martineau at para. 21.

[37] While imperfect or even non-compliance with formal testamentary requirements may be overcome by application of a sufficiently broad curative provision, the further a document departs from the formal requirements the harder it may be for the court to find it embodies the deceased’s testamentary intention: George at para. 81.

The Material Time

[37] In many cases, as here, the material time for determining testamentary intentions on a s. 58 application is the time when the document in question was created. However, as noted in Estate of Young, depending on the circumstances, the material time may vary on this key issue. For example, after creating a document, a will-maker may, by words or actions, manifest a fixed and final intention that it expresses how his or her property is to be disposed of on death and thus that it operates as a will. In other words, a document may acquire a testamentary character by subsequent and sufficient manifestation of the will-maker’s intention: Bennett et al. v. Toronto General Trusts Corporation, [1958] S.C.R. 392 at 397. Nevertheless, in most cases, the focus of inquiry will be the will-maker’s intention when the document was prepared and executed: see, for example, Sweeney Cunningham Estate v. Sweeney, 2013 NSSC 299 at para. 29; Komonen v. Fong, 2011 NSSC 315 at para. 23.

The Scope of Admissible Extrinsic Evidence

[38] The WESA does not indicate what evidence is admissible on a s. 58 inquiry. Accordingly, the ordinary rules of admissibility apply.

[39] Ordinarily, evidence must be relevant to a live issue and not be subject to exclusion under any other rule of law or policy to be admissible: Sidney N. Lederman, Alan W. Bryant and Michelle K. Fuerst, The Law of Evidence in Canada 4th ed. (Markham: LexisNexis Canada Inc., 2014) at §2.40. Relevance must, therefore, be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Mr. Justice Rothstein affirmed the meaning of “relevance” in R. v. White, 2011 SCC 13:

36 … In order for evidence to satisfy the standard of relevance, it must have “some tendency as a matter of logic and human experience to make the proposition for which it is advanced more likely than that proposition would be in the absence of that evidence” [citations omitted].

37 … to say that an item of evidence is not relevant; that it is not probative of a live issue; or that it is “equally explained by” or “equally consistent with” either determination of a live issue are three ways of saying the same thing.

[40] Sitting as a court of probate, the court’s task on a s. 58 inquiry is to determine, on a balance of probabilities, whether a non-compliant document embodies the deceased’s testamentary intentions at whatever time is material. The task is inherently challenging because the person best able to speak to these intentions – the deceased – is not available to testify. In addition, by their nature, the sorts of documents being assessed will likely not have been created with legal assistance. Given this context and subject to the ordinary rules of evidence, the court will benefit from learning as much as possible about all that could illuminate the deceased’s state of mind, understanding and intention regarding the document. Accordingly, extrinsic evidence of testamentary intent is admissible on the inquiry: Langseth Estate v. Gardiner (1990), 75 D.L.R. (4th) 25 at 33 (Man. C.A.); Yaremkewich Estate (Re) at para. 32; George. As is apparent from the case authorities, this may well include extrinsic evidence of events that occurred before, when and after the document was created: see, for example, Bennett; George; Estate of Young; Re MacLennan Estate (1986), 22 E.T.R. 22 at 33 (Ont. Surr. Ct.); Caule v. Brophy (1993), 50 E.T.R. 122 at paras. 37–44 (Nfld. S.C.).

The Judge’s Treatment of the Evidence

[41] The judge conducted her s. 58 inquiry in a thorough, careful, transparent manner. She considered the words and form of the 2014 Will in detail, together with the large and varied body of extrinsic evidence of events that occurred before, when and after it was made. The focus of her analysis was Ms. Hadley’s intention when she wrote the 2014 Will, which was the material time for s. 58 purposes. On balance, she concluded that it did not represent a deliberate and final expression of Ms. Hadley’s testamentary intentions, which conclusion, though not inevitable, was reasonably available on the evidence as a whole.

[42] In her reasons, the judge listed or had previously noted virtually all of the factors characterized by the appellants as genuinely probative of the central issue. However, after balancing those factors with others to contrary effect, she simply was not persuaded by their arguments or the validity of their position. I see no error in the manner in which she reached this conclusion or in her interpretation of the evidence and its overall import.

[43] Contrary to the appellants’ submission, the evidence the judge relied upon to support her conclusion was relevant to Ms. Hadley’s testamentary intentions when the 2014 Will was written. While not necessarily dispositive, each item of impugned evidence tended to increase the likelihood that the 2014 Will did not express her final intentions for the disposal of her property on death. For example, although she was not obliged to leave bequests to her nieces, she had previously done so in the 2008 Will and an explanation for the change and some form of express revocation might reasonably have been expected, but both were absent: see McNeil v. Snidor Estate, 2008 MBQB 187 at paras. 21, 23. As a matter of logic and human experience, their absence tended to make it more likely that the 2014 Will did not express Ms. Hadley’s final intentions than it would have been if there was evidence of either or both.