The Duties of an Executor Under a Will

Duties of Executor is an example of one of the many excellent publications that the Canadian bar Dial- A Lawyer library has for free public access.

I have reprinted this article from the said library as it is an excellent summary of the daunting task faced by many executors.

The Dial-A-Law library is prepared by lawyers and gives practical information on many areas of law in British Columbia. Script 178 gives information only, not legal advice. If you have a legal problem or need legal advice, you should speak to a lawyer. For the name of a lawyer to consult, call the Lawyer Referral Service at 604.687.3221 in the lower mainland or 1.800.663.1919 elsewhere in British Columbia.

This script discusses your duties as an executor under a will and what you have to do to probate an estate.

What does it mean to probate an estate?

Probate is the process of getting the court to rule that a will is legally valid. With some exceptions, the estate consists of any land, house, money, investments, personal items and other assets that the deceased owned. The person who died and made the will is called the “testator”.

What is an executor, and what does the executor do?

The executor is named in a will, in general, the executor gathers up the estate assets, pays the deceased’s debts, and divides what remains of the deceased’s estate among the beneficiaries.

How do you confirm that you were named as the executor?

You need to get the original version of the will to check this. If it’s not at the deceased testator’s home, the will may be in a safety deposit box, at the office of the lawyer who drafted the will, or it may be found by a search with the Vital Statistics Agency.

To look in the safety deposit box, phone the bank and make an appointment. Take the key, a death certificate and your own identification. If the will is there and names you as executor, the bank will let you take the will. You and a bank employee will then list the contents of the safety deposit box. You need to keep a copy of that list.

The other thing you can do is search for a wills notice at the Vital Statistics Agency. The testator or the testator’s lawyer may have registered a wills notice with Vital Statistics. This notice tells where the testator planned to keep the original will. If a wills notice was registered, you’ll be able to locate and obtain the original version of the will and confirm that you were named as the executor. For the Vital Statistics Agency office closest to you, call 250.952.2681 or check the Vital Statistics website at www.vs.gov.bc.ca.

Decide if you want to be the executor

If you haven’t yet dealt with any of the estate assets, you cannot be made to act as the executor. Acting as an executor can be very challenging, and you should only take on this responsibility knowing that the task will be time-consuming and stressful. Once you begin the process of dealing with the estate assets, you’re legally bound to complete the job, and you can only be relieved of your responsibility by a court order.

Consider hiring a lawyer

If you decide to act as the executor, consider whether to hire a lawyer to do the paperwork and advise you of your obligations. If you do, the estate pays the lawyer’s fees. Ask the lawyer how the legal fees will be calculated, whether as a percentage of the estate or on an hourly basis. But because unexpected matters often arise in estates, it may not be possible to get an exact estimate of the fees. It’s a good idea to hire a lawyer for any estate involving the distribution of assets through a will, where a grant of probate is required. For most estates, it’s also a good idea to also hire an accountant to help with the several tax returns that need to be filed, as proper filing of returns and payment of taxes is one of the executor’s responsibilities.

Your first decision as executor may be about funeral arrangements

The funeral is your responsibility, although you’ll want to consider the wishes of the deceased person and their relatives. The funeral parlor will ordinarily order you copies of the death certificate. You may take the funeral bills to the bank where the deceased kept an account. If there’s enough money in the account, the bank will give you a cheque from that account to pay the expenses.

You must also confirm that the will is the deceased’s last will

You can confirm this by checking with the Vital Statistics Agency at the office closest to you. Most lawyers send a wills notice to Vital Statistics for every will they prepare. Vital Statistics will then send you a Certificate of Wills Search. This tells you if there’s a record of the will and where the will is kept. You need this certificate when you apply to the court for probate, if you can’t find the original will, the search results may help you locate it.

Cancel charge cards and protect the estate

You should cancel ail the deceased person’s charge accounts and subscriptions. Also ensure that the estate is protected. Make sure valuables are safe and that sufficient insurance is in place. You should immediately change the locks on the apartment or house, and put any valuable things into storage. As for insurance, most insurance policies are cancelled automatically if a house is vacant for more than 30 days, so ask the insurance agent about a “vacancy permit.”

All potential beneficiaries must be notified

The Supreme Court Civil Rules and the new Wilis, Estates and Succession Act (WESA) require that all beneficiaries (as well as certain family members who would be heirs if there was no will, or who are eligible to apply to the court to change the will) must be given a written notice, plus a copy of the will. This is generally done by the estate’s lawyer.

The next step is to prepare and submit the necessary probate documents

The probate documents are submitted to court to get probate. Usually, you must get probate of the will to handle the deceased’s estate. You’ll also have to pay the probate fees as assessed by the court registry. The deceased’s bank will usually allow you to take these funds out of the deceased’s account.

Be aware that you don’t always have to apply for probate

It depends on the type of assets in the estate. Certain assets can be passed down without requiring probate. Land owned in joint tenancy with another person doesn’t require probate. If the deceased person owned land or a house in joint tenancy with another person, you only have to file an application in the Land Titles Office along with the death certificate. This will register the land in the name of the surviving joint tenant.

Also, probate isn’t required for joint bank accounts or vehicles owned jointly. Again, the death certificate is usually sufficient to transfer these to the surviving joint owner.

In addition, RRSPs and insurance policies, which typically name a beneficiary to receive the proceeds in case of the person’s death, aren’t considered part of the estate, and therefore don’t require probate. You should give the death certificate to any insurance companies and RRSP administrators that the deceased person had plans with.

They’ll want the death certificate before paying money to a beneficiary.

What about stocks and bonds?

If the estate includes securities, such as stocks and bonds, you may have to apply for probate in order to transfer them. You should check with the financial institution or transfer agent involved for each security in the estate because they’ll have different requirements.

Also deal with any pensions the deceased had

If the deceased paid into the Canada Pension Plan, immediately apply to your local CPP office to tell them of the death and obtain any death, survivor or orphan benefits. Most funeral directors can provide you with information and forms regarding CPP death benefits. You should also check with the deceased person’s employer about any benefits available there. If the deceased was receiving an old age security pension or other pensions, you also need to tell those pension offices of the death. Note that any CPP or old age security cheques for the month after the month in which the person died must be returned uncashed.

Certain income tax returns must be filed, and income tax may have to be paid

You need to file tax returns for any years for which the deceased didn’t file a return. If the estate made any income after the date of death (such as rental income or interest on.bank accounts), then tax returns will have to be filed for the estate for each year after death, until the estate is wound up or paid out. The estate must pay taxes and obtain a Clearance Certificate from Revenue Canada before the estate can be distributed to the beneficiaries. This certificate confirms that all income taxes or fees of the estate are paid. This is an important step because the tax department can potentially impose taxes that you don’t know about.

Now you can pay the estate’s debts

Depending on the circumstances, you may want to advertise for possible creditors so you can make sure all legitimate debts are paid. This is to protect yourself against creditor claims that arise after you distribute the estate. As the executor, you could be personally liable if you don’t pay the deceased’s debts, includig any taxes owed, before you distribute the estate. You should talk to a lawyer about this.

Be aware of the WiUs Variation Act

The Wills Variation Act allows any child or spouse of the deceased to apply to the court to vary or change the terms of the will. This Act has a six-month deadline (starting from the granting of probate). You should wait for six months to distribute the assets or obtain releases from each potential claimant. Remember that you are responsible if you distribute the assets to the wrong people and could be sued.

Get tax clearance

It’s wise to obtain a tax clearance certificate from the Canada Revenue Agency. This certificate confirms that all income taxes or fees of the estate are paid. This is an important step because the tax department can potentially impose taxes that you don’t know about.

Finally, you’re ready to distribute the estate to the beneficiaries

But before distributing the assets as directed in the will, you should submit a full accounting of the estate’s financial activities and obtain a release from each beneficiary. Your accounting will usually include a claim for reimbursement of expenses you’ve paid yourself. You’ll have to decide if you also want to claim a fee for acting as executor. This fee can be up to 5% of the estate and is taxable income. If you want to claim a fee, the amount you claim should be included in the accounting that you send to the beneficiaries.

Where can you find more information?

• See the booklet “Being an Executor” produced by the People’s Law School, available online through Clicklaw. -at www.clicklaw.bc.ca/resource/1022.

• Also see the BC Ministry of Justice’s website on wills and estates at www.ag.gov.bc.ca/courts/other/wills estates.htm. [updated April 2014]

Dial-A-Law© is a library of legal information that is available by:

• phone, as recorded scripts, and

• audio and text, on the CBA BC Branch website.

To access Dial-A-Law, call 604.687.4680 in the lower mainland or 1.800.565.5297 elsewhere in BC. Dial-A-Law is available online at www.dialalaw.org.

The Dial-A-Law library is prepared by lawyers and gives practical information on many areas of law in British Columbia. Dial-A-Law is funded by the Law Foundation of British Columbia and sponsored by the Canadian Bar Association, British Columbia Branch.

Executor/Trustees Fees

Zadra v Cortese 2016 BCSC 390 dealt with a passing of executor’s accounts before a registrar to determine the amount of executor/trustees fees for handling a complex estate for ten years but delegating most of the work to professionals.

The value of the estate increased from $800,000 to $4.8 million over this time due to the rise in the real estate market.

The registrar allowed fees of %3 of the gross estate, plus %3 of the estate’s income and a management fee of $12,000.

The executor had pre- taken fees of $70,000 but was not admonished for it as it was done in the belief that the executor was entitled to it.

The Court Stated:

41 Sections 88 and 89 of the Trustee Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 464, provide as follows:

88 (1) A trustee under a deed, settlement or will, an executor or administrator, a guardian appointed by any court, a testamentary guardian, or any other trustee, however the trust is created, is entitled to, and it is lawful for the Supreme Court, or a registrar of that court if so directed by the court, to allow him or her a fair and reasonable allowance, not exceeding 5% on the gross aggregate value, including capital and income, of all the assets of the estate by way of remuneration for his or her care, pains and trouble and his or her time spent in and about the trusteeship, executorship, guardianship or administration of the estate and effects vested in him or her under any will or grant of administration, and in administering, disposing of and arranging and settling the same, and generally in arranging and settling the affairs of the estate as the court, or a registrar of the court if so directed by the court thinks proper.

(2) The court or a registrar of the court if so directed by the court, may make an order under subsection (1) from time to time, and the amount of remuneration must be allowed to an executor, trustee, guardian or administrator, in passing his or her accounts, in addition to any other allowances for expenses actually incurred to which the trustee, executor, guardian or administrator may by law be entitled.

(3) A person entitled to an allowance under subsection (1) may apply annually to the Supreme Court for a care and management fee and the court may allow a fee not exceeding 0.4% of the average market value of the assets.

89 The court may, on application to it for the purpose, settle or direct the registrar to settle the amount of the compensation, although the estate is not before the court in an action.

42 The administrator is entitled to remuneration for his work on the estate to a maximum of 5% of the gross aggregate value, including capital and income of all the assets of the estate at the date of passing, pursuant to s. 88(1) of the Trustee Act. The criteria to be considered in determining the amount of remuneration which should be awarded are set out in the much cited case of Toronto General Trusts Corp. v. Central Ontario Railway (1905), 6 O.W.R. 350 (Ont. H.C.) at para. 23wherein the Court states:

[23] From the American and Canadian precedents, based upon statutory provision for compensation to trustees, the following circumstances appear proper to be taken into consideration in fixing the amount of compensation:

(1) the magnitude of the trust;

(2) the care and responsibility springing therefrom;

(3) the time occupied in performing its duties;

(4) the skill and ability displayed;

(5) the success which has attended its administration.

43 It is not required that remuneration be fixed at a specific percentage of the gross value of the estate, it can be calculated as a lump sum provided it does not exceed 5%. In Turley, Re (1955), 16 W.W.R. 72 (B.C. S.C.) at para. 11 the Court stated:

[11] As to grounds 1 and 2 of this application, I think the principles to be applied are well settled. I adopt the statement of the principles as given in, I think, all the cases and found in Re Atkinson Estate [1952] OR 688, that the compensation allowed an executor is to be a fair and reasonable allowance for his care, pains and trouble and his time expended in or about the estate. Both responsibility and actual work done are matters for consideration and, while there should not be a rigid adherence to fixed percentages, they are to be used as a guide. I think that the factors I mentioned in my judgment on the previous motion are found here. It is not only the presence of continuing trusts that makes the realization and administration of estates difficult. It is submitted that the capital fee should be charged only on the amount realized, excluding those assets that go over in specie. While the fact that considerable portions of the estate are transferred in specie is a factor the registrar may consider in settling the percentage he allows, I think it would be quite inappropriate as a rule to exclude these in the computation of aggregate value. There appears to be evidence here of extensive work. It is the duty of the executor to administer the whole of the estate. His work in some things might not be compensated sufficiently by a percentage much in excess of the maximum allowed.

44 Maximum remuneration is not awarded as a matter of routine. Appropriate remuneration is a matter of what is fair and reasonable in all the circumstances. As stated by the B.C.C.A, in Kanee Estate, Re [1991 CarswellBC 654 (B.C. C.A.)] (19 September 1991), Vancouver Registry CA014168:

Maximum remuneration does not go as a matter of course and it is to be expected that there will be disputes over the quantum of remuneration. Section 90(1) does not prescribe an adversarial process. There are no plaintiffs, no defendants, no pleadings, no discoveries, no provisions for offers of settlement or payment into Court, and no other trappings of an adversarial nature, All interested parties are entitled to be heard but in the end the officers of the Court must decide what is fair and reasonable in all of the circumstances.

45 The amount of remuneration to be paid to the administrator is determined on a quantum merit basis which reflects the reasonable value of the services rendered, which is subject to a 5% maximum.

46 In this regard, evidence is required concerning the administrator’s experience in estate matters, the nature of the estate, the tasks undertaken, the time spent, unusual problems arising during the administration of the estate, the skill employed by the administrator, and the results achieved which were directly attributable to the administrator’s efforts. Documentary evidence and time records should be provided where they exist. The administrator provided this evidence over the course of days of testimony. In addition, extensive documentary evidence was provided by both the administrator and the beneficiaries. However, no time records were provided, as the administrator did not keep a record in this regard.

47 An inference may be drawn against an administrator for failure to provide time records in appropriate circumstances. See Lowe Estate, Re, 2002 BCSC 813 (B.C. S.C.) at para. 33.

48 A negative inference in this regard will be appropriate where criticisms in the administrator’s administration of the estate are found to be valid. In these circumstances, the administrator’s remuneration may be substantially reduced. See Lowe Estate, Re , supra, at paras. 27, 28, 41 and 42.

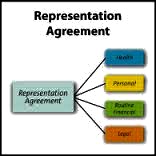

Court Termination of Representation Agreements

Baker-McGrotty v Baker 2016 BCSC 699 discuss when the court will exercise its discretion to NOT terminate representation agreements after the appointment of a committee under the Patients Property Act.

26 Section 19 of the Patients Property act provides as follows:

19 On a person becoming a patient as defined in paragraph (b) of the definition of “patient” in section 1,

(a) every power of attorney given by the person is terminated, and

(b) unless the court orders otherwise, every representation agreement made by the person is terminated.

27 In Lindberg v. Lindberg, 2010 BCSC 1127 (B.C. S.C. [In Chambers]), Mr. Justice Willcock noted that the PPA is silent in relation to the factors the court is to consider in the exercise of its residual discretion to uphold a representation agreement following a declaration of incapacity under the PPA:

[49] The law permits the representation agreement to continue to be effective, despite the onset of disability, and recognizes the autonomous choice of a representative by a patient. The difficulty is that s. 19 of the PPA permits a representation agreement to be saved but does not establish the criteria which should be considered in determining whether or not to exercise that discretion. In the absence of further explicit direction in the legislation, I consider the following factors to be appropriate criteria:

(a) the circumstances in which the representation agreement was executed;

(b) the scope of the representation agreement; and,

(c) the basis for the application to set it aside.

28 The foregoing factors were subsequently adopted by Madam Justice Ross in Dawes v. Dawes, 2012 BCSC 1323 (B.C. S.C.), and there has been no suggestion that these criteria should not apply to the case at bar.

Proprietary Estoppel

NOTE: This Court of Appeal Decision was over turned by the Supreme Court of Canada 2017 SCC 61 and the claim was allowed

See blog entry dated February 2,2018

The BC Appeal Court in Cowper-Smith v Morgan 2016 BCCA 200 allowed an appeal in part to over turn the successful the claim brought for proprietary estoppel at trial by finding that the claim should not be allowed where a non owner of property gave assurances and a reliance thereon with respect to her future intentions based on the assumption she would inherit from her mother the owner., when she might not. Since the sister had no enforceable equitable or legal right to the property at the critical time being when the representation was made, the brother should not have relied upon it.

The deceased mother transferred her house into joint tenancy with her daughter in 2001. In 2002 the mother made a will leaving her estate equally to her three children. The mother’s investment accounts were over several years transferred into joint names with the daughter.

A declaration of trust for the house and bank assets was signed in 2001.

The defendant sister told her siblings that the house was put into her name only so she could assist in their mother’s affairs and would all eventually go to her mother’s estate.

The defendant daughter promised to sell one of her brothers her anticipated 1/3 share in the house to lure him back to Canada to take care of his mother.

The trial and appeal courts over turned the transfers and distributed her estate equally as per her will on the basis of undue influence but the appeal over turned the portion of the judgement that allowed the brother to succeed on the basis that he relied upon the promise made by his sister, he took care of his mother for years, but the sister reneged on her promise to transfer to him her 1/3 of the house as she did not own it when she promised it.

The Appeal Court stated in part:

Commerce International Bank Ltd., [1982] Q.B. 84 (Eng. C.A.) at 122:

When the parties to a transaction proceed on the basis of an underlying assumption (either of fact or of law, and whether due to misrepresentation or mistake, makes no difference), on which they have conducted the dealings between them, neither of them will be allowed to go back on that assumption when it would be unfair or unjust to allow him to do so. If one of them does seek to go back on it, the courts will give the other such remedy as the equity of the case demands.

70 While the principles of fairness and flexibility have informed the modern approach to the application of proprietary estoppel, as adopted by this Court in its jurisprudence (see Idle-O Apartments Inc. v. Charlyn Investments Ltd., 2014 BCCA 451 (B.C. C.A.) at para. 49; Sabey v. von Hopffgarten Estate, 2014 BCCA 360 (B.C. C.A.); Scholz v. Scholz, 2013 BCCA 309 (B.C. C.A.) at para. 31; Sykes v. Rosebery Parklands Development Society, 2011 BCCA 15 (B.C. C.A.) at paras. 44-46; Erickson v. Jones, 2008 BCCA 379 (B.C. C.A.) at paras. 52-57; Trethewey-Edge Dyking (District) v. Coniagas Ranches Ltd. [2003 CarswellBC 657 (B.C. C.A.)] at paras. 64-73; Zelmer v. Victor Projects Ltd. (1997), 34 B.C.L.R. (3d) 125 (B.C. C.A.) at paras. 36-37), there remains a necessary balancing between an overly broad application of the doctrine under the general guise of “unfairness” and an overly narrow application of the doctrine that places excessive weight on the technical requirements of the doctrine. See Lord Scott’s observations in Cobbe v. Yeoman’s Row Management Ltd., [2008] UKHL 55 (U.K. H.L.) in contrast to Lord Neuberger’s comments in Thorner v. Major, [2009] UKHL 18 (U.K. H.L.).

71 These underlying rationales and explanations for the evolution of the doctrine have led to its modern iteration as enunciated by Madam Justice Bennett in Sabey and affirmed by Madam Justice Newbury in Idle-O Apartments Inc. at para. 49:

[49] From the foregoing I infer that although proprietary estoppel is, like most equitable remedies, flexible and aimed at doing justice, and although the basic elements of the doctrine are not to be technically confined, those elements must still be made out and an equity established. I reproduce again the encapsulation of the doctrine provided recently in Sabey:

Is an equity established? An equity will be established where:

There was an assurance or representation, attributable to the owner, that the claimant has or will have some right to the property, and

The claimant relied on this assurance to his or her detriment so that it would be unconscionable for the owner to go back on that assurance.

If an equity is established, the court must determine the extent of the equity and the remedy appropriate to satisfy the equity.

72 As was noted by Bennett J.A. in Sabey, the bulk of the analysis occurs at the first stage, where “findings with regard to assurances, reliance and detriment are made” and where the court must determine whether it would be unconscionable for the person “to fail to make good on a promise to create a legal right in favour of someone else” (at para. 27).

73 Thus, the elements of the modern doctrine of proprietary estoppel require:

(i) an assurance or representation by the defendant that leads the claimant to form a mistaken assumption or misapprehension that he or she has an interest in the property at issue;

(ii) a causative connection between the assurance or representation and the claimant’s reliance on the assumption such that the claimant changes his or her course of conduct; (

iii) a detriment suffered by the claimant that flows from his or her reliance on the assumption, which causes the unfairness and underpins the proprietary estoppel; and

(iv) a sufficient property right held by the defendant that could be transferred to satisfy the right claimed by the claimant.

The Majority of the Court held:

98 There is no doubt that the applicable standard of review in this case is that described by Newbury J.A. in Idle-O Apartments Inc. as follows (at para. 72):

[72] At the outset, I note that the granting of a remedy for proprietary estoppel is a discretionary matter that attracts a high degree of appellate [deference]. The classic statement of the applicable standard of review may be found in Friends of the Old Man River Society v. Canada (Minister of Transport), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 3, where the Court quoted with approval the following passage from Charles Osenton & Co. v. Johnston, [1942] A.C. 130 (H.L.):

The law as to the reversal by a court of appeal of an order made by the judge below in the exercise of his discretion is well-established, and any difficulty that arises is due only to the application of well-settled principles in an individual case. The appellate tribunal is not at liberty merely to substitute its own exercise of discretion for the discretion already exercised by the judge. In other words, appellate authorities ought not to reverse the order merely because they would themselves have exercised the original discretion, had it attached to them, in a different way. But if the appellate tribunal reaches the clear conclusion that there has been a wrongful exercise of discretion in that no weight, or no sufficient weight, has been given to relevant considerations such as those urged before us by the appellant, then the reversal of the order on appeal may be justified…(See also Wenngatz v. 371431 Alberta Ltd., 2013 BCCA 225 at para. 9; Stone v. Ellerman, 2009 BCCA 294 at para. 94; and Harper v. Canada (Attorney General), 2000 SCC 57at para. 26.)

99 In considering whether there has been a wrongful exercise of discretion, I begin by noting that in Uglow v. Uglow, [2004] EWCA Civ 987 (Eng. & Wales C.A. (Civil)) at para. 9, the Court of Appeal described the following general principle:

The overriding concern of equity to prevent unconscionable conduct permeates all the different elements of the doctrine of proprietary estoppel; assurance, reliance, detriment and satisfaction are all intertwined.

100 In my view, the assurance given by Gloria to Max in this case was so based on uncertainty as to undermine any claim based on proprietary estoppel and that uncertainty goes to the root of reliance. The uncertainty arises from the fact that both at the time the assurance was given by Gloria and at the time Max acted upon the assurance, the Property was owned by Elizabeth; that is, Gloria had no beneficial interest in the Property and was uncertain what interest she would eventually inherit, if any. In the circumstances, Max cannot have been reasonably certain Gloria could do what she represented she would do. His hope and belief, initiated and encouraged by her, that he would likely be given the opportunity to buy whatever interest Gloria might inherit does not give rise to an interest in his mother’s estate. With respect, I do not agree with Smith J.A.’s view that Gloria’s “clear entitlement to a one-third interest in the Property at the time of the judge’s order” is relevant to whether an estoppel arose when Max acted upon the assurance given to him.

101 In relation to reliance as an essential element of a claim founded upon proprietary estoppel, Snell’s Equity, 31st ed (London: Sweet and Maxwell, 2005) says, at §10-18:

A must have acted in the belief either that he or she already owned a sufficient interest in O’s property to justify the expenditure or that he or she would obtain such an interest although it is not necessary for A to establish that he or she had an expectation in relation to a specific or clearly identified piece of property. But if A has no such belief, and improves land in which he knows he has no interest or merely the interest of the tenant, or licensee or as an occupier who incurs expenditure in the hope of obtaining planning permission and then entering into a contract to buy the land, he or she has no equity in respect of his expenditure. It is not sufficient that A believes he will obtain an interest over O’s property if he is also aware that O may change his mind.

[Emphasis added.]

102 Snell’s Equity proposes that in order to establish the estoppel it is necessary for A to show that O “created or encouraged the belief or expectation on the part of A that O would not withdraw from the agreement in principle”. That is a description of a present and ongoing obligation.

103 The circumstances in the case at bar resemble those in the many reported inheritance cases, including In re Basham and Thorner v. Major, with an important exception: the assurance here did not come from the beneficial owner of the property interest. In my view, the interest found by the judge to have been wrongly obtained through undue influence in respect of the land transfer and Declaration of Trust cannot be regarded as sufficient interest to permit Gloria to make representations or give assurances that might give rise to a proprietary estoppel. The assurance Gloria gave to Max had nothing to do with an interest in the Property created by the transfer or Declaration of Trust (both of which she thought, at the time, to be intended to simply facilitate the handling of the estate). The interest she promised to Max was the right to buy her expected inheritance. She did not yet own that inheritance and might never have come into it.

104 Walker L.J., in the passage from Thorner cited by Smith J.A., was of the view that in order to constitute proprietary estoppel, “the assurances given to the claimant (expressly or impliedly, or, in standing-by cases, tacitly) should relate to identified property owned (or, perhaps, about to be owned) by the defendant” (emphasis added).

105 Walker L.J. does not expand upon his view that an estoppel may arise from assurances made by one who is about to be the owner of the property. Neither the source nor the extent of that qualification to simple ownership is described, other than by a reference later in the paragraph to Crabb v. Arun District Council, in which there is no discussion of property about to be owned by the Council that made the representation in that case. In fact, in Crabb there are repeated references to the legal rights of the person making the representation. Denning M.R. states: “Short of an actual promise, if he, by his words or conduct, so behaves as to lead another to believe that he will not insist on his strict legal rights — knowing or intending that the other will act on that belief — and he does so act, that again will raise an equity in favour of the other; and it is for a court of equity to say in what way the equity may be satisfied” (emphasis added). Scarman L.J., citing Willmott, notes: “the defendant, the possessor of the legal right, must have encouraged the plaintiff in his expenditure of money or in the other acts which he has done, either directly or by abstaining from asserting his legal right” (emphasis added). In short, there is nothing expressly stated in Crabb that contemplates an estoppel arising with respect to property that is other than legally owned by the person making the representation.

106 Even assuming there to be some basis for the view that proprietary estoppel might arise as a result of an assurance given by one about to be the owner of property, I would not expand that class of persons so far as to include a potential beneficiary who gives an assurance to another, years before the death of a testator, with respect to what she will do with an inheritance that she merely anticipates receiving, if the person receiving the assurance acts as requested in the meantime. Not only is there uncertainty, in such a case, with respect to the promisor’s ability to deliver a proprietary interest to the promisee at the time the assurance is given, the uncertainty is not resolved when the promisee acts in reliance upon the promise.

107 Leaving aside, for the moment, the question whether Gloria was in a position to exert undue influence upon her mother, there was uncertainty with respect to the property interest Max was being promised. First, there was uncertainty whether Gloria would inherit anything from her mother. She might have predeceased her mother. Her mother might have changed her will and left Gloria more or less than a one-third interest in the property. Her mother might have sold the house and moved into accommodation more suited to her declining health. Simply by liquidating her property Elizabeth Cowper-Smith would have precluded Max from asserting a right to buy anything from Gloria. Certainly it is not suggested that Elizabeth was in any way restricted in her dealings with the property simply because her daughter made assurances to Max about what she would do on Elizabeth’s death.

108 Without exerting undue influence upon her mother, Gloria was not in a position to determine what property interest Max would receive in exchange for his move to Victoria. The fulfilment of Gloria’s promise was entirely conditional on her mother’s actions, which were outside her control.

109 Further, an obligation on Gloria’s part cannot have arisen before she inherited an interest in the Property. In this case, unlike the inheritance cases, no obligation arose simply as a result of the reliance upon the assurance. Where the assurance comes from the testator, the estoppel arises because there has been such reliance, making it inequitable to permit the testator to resile from the promise. A remedy is available before the testator’s death. As noted by Mummery L.J. in Uglow, proprietary estoppel may be relied upon to prevent a testator from making a will giving specific property to one person, if by his conduct he has previously created the expectation in a different person that he will inherit it:

The testator’s assurance that he will leave specific property to a person by will may thus become irrevocable as a result of the other’s detrimental reliance on the assurance, even though the testator’s power of testamentary disposition to which the assurance is linked is inherently revocable.

110 As Professor MacDougall observes in Estoppel at §6.38, there is a temporal element to proprietary estoppel. The demands of equity and how they are properly satisfied may change over time; but the equity arises when there is reliance. That is the foundation for what he describes at §6.73 as a “more orthodox approach” to the question we face than that which is taken by Smith J.A.:

… [P]roprietary estoppel will not apply where the owner in fact has no existing rights with respect to the property in question when the equity would otherwise arise — i.e., at the time of the detrimental reliance.

111 Uncertainty with respect to the promisor’s ability to fulfill the promise is closely related to the concept of reliance. Key to the acquisition of a proprietary interest by estoppel is the principle that it is unconscionable to permit a person to fail to keep a promise made and reasonably relied upon by the promisee. How can there be reasonable reliance upon a promise to convey an interest in property made by one who does not have such an interest or whose interest is uncertain?

112 Like my colleague, I recognize the evolution of the law of proprietary estoppel has been marked by tensions between, on the one hand, broad principles of flexibility and fairness, and on the other hand, narrow technical requirements. While the jurisprudence tells us that proprietary estoppel is no longer a “Procrustean bed constructed from some unalterable criteria” (see Idle-O Apartments Inc. at para. 23), the Court in Crabb nonetheless insisted the exercise of equitable jurisdiction be rooted in identifiable principles. To that end, the Court adopted the words of Harman L.J. in Bridge v. Campbell Discount Co., [1961] 1 Q.B. 445 (Eng. C.A.) at 459:

Equitable principles are … perhaps rather too often bandied about in common law courts as though the Chancellor still had only the length of his own foot to measure when coming to a conclusion. Since the time of Lord Eldon the system of equity for good or evil has been a very precise one, and equitable jurisdiction is exercised on well-known principles.

113 I do not read this Court’s judgment in Idle-O Apartments Inc. as suggesting that uncertainty that undermines reliance on a representation may be disregarded. To the contrary, when the Court considered whether an equity was established (at para. 23) it required the claimant to establish he believed in the existence of “a right created or encouraged by the words or the actions of the other party such that it would be unfair, unjust or unconscionable to allow the representor to set up its undoubted rights against the claimant”. At para. 57, the Court referred with approval to the trial judge’s recognition that detrimental reliance on the part of the claimant “underpins the claim and establishes the unfairness or unjustness that ought to be addressed by equity. Without such, … the doctrine may become ‘somewhat pointless’ and a ‘circumlocution for doing justice’.”

114 Newbury J.A., after describing the evolving conception of the scope of proprietary estoppel, noted:

[48] This court has adopted the “broader” approach to proprietary estoppel: see Zelmer at para. 49, Erickson at paras. 55-7, and most recently in Sabey at paras. 28-9. This approach is consistent with the judgment of Lord Denning in the seminal English case of Crabb v. Arun District Council, [1976] 1 Ch. D. 179 at 187-9; Oliver J. in Taylor Fashions; Buckley L.J. in Shaw v. Applegate, [1978] 1 All E.R. 123 at 130-1; and various other English authorities. On the other hand, English and Australian courts (and to some extent Canadian courts) have in recent years been at pains to emphasize that proprietary estoppel does not arise simply out of conduct that a court finds to be unconscionable. As observed by Lord Scott in Yeoman’s Row Management Ltd v. Cobbe, [2008] UKHL 55:

… unconscionability of conduct may well lead to a remedy but, in my opinion, proprietary estoppel cannot be the route to it unless the ingredients for a proprietary estoppel are present. These ingredients should include, in principle, a proprietary claim made by a claimant and an answer to that claim based on some fact, or some point of mixed fact and law, that the person against whom the claim is made can be estopped from asserting. To treat a “proprietary estoppel equity” as requiring neither a proprietary claim by the claimant nor an estoppel against the defendant but simply unconscionable behaviour is, in my respectful opinion, a recipe for confusion. [At para. 16.]

[Emphasis added.]

115 Professor MacDougall, at §6.34, echoes Lord Scott’s concerns, suggesting the doctrine of proprietary estoppel “should not be seen as a generalized remedial doctrine for unfairness.” Unfairness, in MacDougall’s view, is merely a general description of what the doctrine seeks to combat. Unfairness is not, in itself, an “overarching principle” that allows proprietary estoppel to be applied even in the absence of the typical requirements.

116 The Court in Idle-O Apartments Inc. further noted that the test for establishing a proprietary estoppel had recently been collapsed, in Sabey, into two components (see para. 30):

There was an assurance or representation, attributable to the owner, that the claimant has or will have some right to the property, and

The claimant relied on this assurance to his or her detriment so that it would be unconscionable for the owner to go back on that assurance.

[Emphasis added.]

117 While the criteria that define the limits of proprietary estoppel are not unalterable, I see no reason in principle why the cause of action should be expanded to permit a person to acquire an interest in property by reliance upon an assurance by a non-owner that falls short of a contractual obligation. Such an expansion would be problematic, untying entirely from its ties to property the only estoppel that can be used as a sword. I would not so extend the cause of action.

118 In my view, the fact Gloria used undue influence to obtain de facto control over the Property and Investments does not affect that conclusion. Max did not, in fact, rely upon that undue influence as assurance that Gloria would deliver on her promise. Even if he had known of the influence exerted by Gloria, equity should not come to the assistance of one who says he arranged his affairs in reliance upon a promise made by a person exerting improper control over a testator with respect to what she would do with the inheritance assured by the exercise of that control. In fairness to him it should be said that Max is not advancing that argument. Even so, the logic of that argument lies at the root of the proposition that undue influence distinguishes this case from others where a non-owner makes assurances about what rights an owner will exercise over property.

Conclusion

119 In the result, I would allow the appeal on this aspect of the order only and set aside the Order made in Max’s favour. In all other respects, I agree with my colleague’s reasons and conclusions.

Saunders J.A.:

I AGREE:

Appeal allowed in part.

WESA: Forcing the Executor to Act & Rule 25-11

Forcing Executor to Act. Rule 25-11 of WESA permits ‘a person interested in the estate’ to use a Citation to compel the named executor to apply for probate or be deemed to have renounced.

This is an important tool in the arsenal of estate litigators when dealing with parties who for often unknown reasons refuse to proceed with the task of taking control of the deceased’s assets and affairs, getting the will probated, the debts paid, and the assets distributed to the beneficiaries.

Rule 25-1 (4) provides that an executor renounces executorship upon two circumstances:

- in the circumstances set out under paragraph 25 – 11 (5) where the executor is deem to have renounced executorship following a citation to apply for probate;

- when a Notice of Renunciation in Form 17 from the executor is filed in the relevant application or proceeding. There is now a prescribed notice of renunciation.

Since Rule 25-11 permits ” a person interested in the estate” to issue a Citation, so it is certainly arguable that the citation process will be available to not just named executors, beneficiaries, and creditors, but also to intestate heirs and potential wills variation claimants.

The Citation is issued in Form P32 of the WESA Rules.

The Citation must clearly identify the citor, the deceased, and the document which is to be probated as the will, as well as the citor1 s grounds for believing that the document exists.

The citation must be personally served and is not filed with the court registry to commence the Citation process .

If the cited executor does apply for the grant, it is still open to the citor to apply under s. 158 of the WESA to remove or pass over the executor under appropriate circumstances.

The executor served with the Citation must, within 14 days after being served provide a copy of the grant of probate by ordinary mail, or if no probate has yet been granted, then serve the Citor as follows:

- if they have submitted the probate documents to the registry, then provide by ordinary mail copies of the documents ;

- file an answer and form 33 stating that the cited person will either apply for a grant of probate or refuses to apply for a grant of probate .

Under rule 25 – 11 (5) a person who is cited to apply for a grant of probate is deemed to have renounced executorship to that document unless the grant of probate is obtained within six months after the date in which the citation was served, or within any longer. The court on application by the cited party may allow, or has filed an answer stating that the executor refuses to apply for a grant of probate in respect of the testamentary document.

The standard 21 day notice of the application for probate will use up a significant portion of that six month period .

Any issue concerning the validity of the will or another impediment such as a notice of dispute, then the time period would be impossible to meet.

It is likely that in such scenarios that a court applications to extend the time period would be necessary.

Signing a Trustee Release

Anyone practicing law in wills and estates, or who has inherited monies, will be familiar with being required to sign a Trustee Release before the funds are disbursed to the beneficiaries.

In BC, it is simply the way business is conducted, and it saves a great deal of time and expense by not forcing the executor/trustee to pass accounts firstly before distributing the assets.

Thus I was somewhat surprised to read the following extract from Bronson v Hewitt 2010 BCSC 169:

The Trustee’s entitlement to demand a release does not arise for the first time in this action. The first reported case dates back to 1845. In Chadwick v. Heatley (1845) S.C. 2 Col. 137, 63 E.R. 671, the trustee sought to distribute trust funds to surviving beneficiaries. He offered a general release as a condition to the payment which the plaintiff refused to sign. The court concluded the trustee did not have the right to insist on having the release executed.

[655] In King v. Mullins (1852), 61 E.R. 469, the court held that although it was usual practice to give a release in order to discharge a trustee, a trustee paying in accordance with the letter of the trust has no right to require a release.

[656] In Brighter v. Brighter Estates, [1998] O.J. No. 3144 (Ct. J. (Gen. Div.)), the court was most critical of the executor requiring a release. The court said at para. 9:

… An executor’s duty is to carry out the instructions contained in the will … [T]he executor has no right to hold any portion of the distributable assets hostage in order to extort from a beneficiary an approval or release of the executor’s performance of duties as trustee, or the executor’s compensation or fee. It is quite proper for an executor (or trustee, to use the current expression) to accompany payment with a release which the beneficiary is requested to execute. But it is quite another matter for the trustee to require execution of the release before making payment; that is manifestly improper.

[657] In Rooney Estate v. Stewart Estate, [2007] O.J. No. 3944 (Sup. Ct. J.) the court noted at para. 39: “[t]he manner of sending the release first and the cheque later suggests the “beneficiary was held hostage for the release.”

[658] In spite of the judicial criticism, a review of British Columbia practice manuals and Continuing Legal Education (“CLE”) publications suggests that it is a common practice to seek a release prior to distribution: R.C. DiBella, Wills and Estate Planning Basics – How to Administer an Estate from Collecting the Assets to Paying Accounts, Materials prepared for CLE Seminar, Vancouver, B.C., October 2006; Gabrielle Komorowska, Guide to Wills and Estates, British Columbia ed. (Gibsons: Evin Ross Publications 1996); British Columbia Probate and Estate Administration Practice Manual, vol. 2, 2d ed. (Vancouver: CLE BC, 2007).

[659] The alternative to obtaining a release is for the trustee to pass his accounts. The passing of accounts will release a trustee from future obligations. For a trustee to request a release of future claims is not in itself objectionable. In this case, however, the proffered document seeks not only a release of future claims but also that the beneficiaries indemnify and hold harmless Howard from any claims arising subsequent to September 30, 2002. A request for an indemnity and hold harmless agreement goes well beyond the type of release referenced in the B.C. practice manuals. In addition, the Distribution Letter suggests that the beneficiaries must sign the Release before any cheque will be forthcoming.

[660] While a request for a release and indemnity in that form may be objectionable, it does not in the first instance create any loss or damage. If all of the beneficiaries had been prepared to sign the Release, matters would have been resolved. They, of course, were not.

[661] What happened subsequently is a matter of greater concern. That signing the Release was a condition of being paid became clear when only those who signed the Release were paid. Under the terms of the trust, distributions were to be made equally. That did not happen. Only those who signed the Release got paid.

[662] The submission that the trustee was entitled to pay certain beneficiaries and accumulate for others is, with respect, untenable. It is contrary to the terms of the BNT Trust Agreement. Further, it is clear that the trustee was not in this case exercising a good faith discretion in accumulating for some beneficiaries and paying others. The only reason the plaintiff beneficiaries were not paid was because they were not prepared to sign the Release, a document that the trustee was not entitled to demand.

[663] By paying certain beneficiaries and not others, Howard breached the terms of the BNT. As soon as Howard paid certain beneficiaries, he was legally obliged to pay the others, regardless of whether or not they were prepared to sign the Release. Although he may have been entitled to hold all of the funds pending a passing of accounts, what he could not do, given the terms of this trust, was to pay some beneficiaries and not others.

[664] It is a principle of equity that equity will not suffer a wrong to be done without a remedy: John McGhee, Snell’s Equity, 31st ed. (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 2005).

Liability of Trustees

Daum v Clapci 2016 BCCA 176 recently discussed the liability of a trustee for failing to properly insure a hotel that burned stating inter alia.

The test for liability is essentially one of honesty and reasonable man prudence in administering the estate affairs as if they were his or her own.

THE LAW

23 The trial judge described Mr. Clapci’s decision to eliminate replacement insurance coverage for the Hotel as “recklessness”, but he found that this conduct was not linked to Mr. Clapci’s duties as a trustee and therefore did not constitute a breach of trust. In reaching that conclusion, the trial judge relied on Waters’ Law of Trust in Canada, 4th ed., at page 932 and following.

24 Professor Waters at pages 931 and 932 states that “[t]he duty of loyalty requires the avoidance of situations where that duty conflicts with the self-interest of the fiduciary” but “should not encompass activities which are so remote from the task undertaken that they could not in any reasonable assessment be said to be forbidden”.

Equity has come to take the view that the solution is provided by an examination of the scope of the agency or task undertaken. If the person who owes fiduciary duties is acting outside the scope of the task he has undertaken – that is, in a manner which has nothing to do with his task – then he will not be required to hand over to the principal any profit which he has made or to desist from any intended activity which would render him profit.

Even by narrowing the principle in this way, however, there are bound to be difficult questions of fact as to whether the particular fiduciary was indeed in the circumstances acting within the scope of his activity when he made a profit for himself, or was positioning himself to make such an intended profit. But the difficult questions of fact which have ceaselessly troubled the courts cannot be avoided; they are inseparable from the application of the principle of conflict of interest and duty.

Professor Waters notes at page 906:

[A] trustee must act honestly and with that level of skill and prudence which would be expected of the reasonable man of business administering his own affairs.

Company Director is a Fiduciary

It is common in estate disputes to encounter a party attempting to deal inappropriately with the affairs of a limited company whose shares should be an estate asset, and when this occurs, one should look for a breach of the directors fiduciary duty owed to the company.

The fiduciary duty of a director to the company is one of loyalty ,good faith, avoidance of conflict of duty and self-interest.

The leading case in this area is Canadian Aero Services Ltd v O’Malley 1974 SCR 592 where the court found senior management who had left the plaintiff with confidential information were fiduciaries and that duty continued after their employment ceased.

Executor Cannot Use Estate Funds To Defend Personally

In a Wills variation claim (now section 60, WESA) an executor cannot use estate funds to defend him or herself if a beneficiary, and may use reasonable estate funds to defend the claim but only in the capacity of executor and not beneficiary.

In a wills variation claim the executor cannot use estate funds to defend his personal interests.

The executor may have his reasonable legal fees paid in his role as executor but should have separate counsel in most cases and the fees should be kept to a minimum–typically for advising on estate developments, liabilities and assets.

Generally, the executor is required to play a neutral role in litigation, and as a result of having to play a neutral role, the executor is generally entitled to special costs from estate.

But when the executor is also a beneficiary the costs must be separated.

If one counsel acts for the executor in both the capacity of executor and personal beneficiary, then the legal fees must be apportioned between the two separate roles, with the estate paying only for the role of executor. Wilcox v Wilcox 2002 BCCA 574.

Steernberg v. Steernberg Estate (2007), 33 E.T.R. (3d) 78, 74 B.C.L.R. (4th) 126, 40 R.F.L. (6th) 106, 2007 BCSC 953, 2007 CarswellBC 1533, Martinson J. (B.C. S.C.); additional reasons to (2006), 2006 CarswellBC 2751, 32 R.F.L. (6th) 62, 28 E.T.R. (3d) 1, 2006 BCSC 1672, [2006] B.C.J. No. 2925, D. Martinson J. (B.C.S.C.) is one of my favourite cases, primarily for the reason in the headnote.

Prior to this case, it was not uncommon for defendants to routinely use estate funds in the hope of depriving a plaintiff of sufficient resources to continue the fight.

Steernberg levels the playing field by making each party pay for their own legal costs as the litigation proceeds, save for the executor, who must remain neutral in the litigation.

Here are the facts of Steernberg:

The Wife, husband’s son, husband’s three daughters and husband’s brother-in-law were beneficiaries under husband’s will.

The Plaintiff wife challenged husband’s will–husband’s son was the executor of the will.

An offer to settle made under R. 37 of Rules of Court, 1990 was signed by son as executor and the other four beneficiaries, but not on behalf of son in his personal capacity as beneficiary.

Legal fees for defendant’ litigation counsel of $148,250.62 and legal fees of counsel for executor of $72,895.24 were deducted before net values of estate were calculated.

Shortly after the trial ended and before reasons for judgment were issued, the estate paid defendants’ litigation counsel’s invoice of $60,700.

None of these payments were made or recorded with the wife’s consent and no funds from estate were made available to the wife before, during or after trial for her legal fees.

During the trial, the wife raised the concern that the defendants took substantial sums of money out of estate for legal fees to defend action before the trial started.

The parties agreed that the issue would be decided after the court gave its decision on whether will should be varied.

It was inappropriate to withdraw funds from estate at start of litigation, or throughout the course of litigation to fund defence of Wills Variation Act claim in the absence of a court order or unanimous agreement of beneficiaries

In a Wills Variation Act (S. 60 WESA) claim the validity of will itself was not being challenged and there was no need for the executor to “defend” will

The son was not entitled, in his neutral role as executor, to make a R. 37 offer and he did not join in the offer in his personal capacity as a beneficiary.

It was not an offer made on behalf of all persons beneficially interested in the assets of the estate and hence would not be binding on the estate.

The losing beneficiaries must pay the wife’s costs personally, not out of the estate.

It was directed that the executor pass his accounts before a registrar and that the registrar inquire into and make recommendations with respect to the net value of the estate after taking into account appropriate legal fees and income that ought to have been earned on the funds had they remained invested.