1. INTRODUCTION

I always fell asleep during my law school trusts class. I could never have imagined then what an important role trusts would come to play in my day-to-day career as a Wills and Estates lawyer. I suspect that there are many other lawyers, notaries and estate planners who have sometimes been mystified about this area of law.

Over the years the use of trusts has grown dramatically to the point that they are now a major cornerstone of estate planning and commercial law. The purpose of this article is to attempt to explain some basic trust principles, with an emphasis on the use of discretionary trusts in estate planning.

2. WHAT IS A TRUST?

Trusts have been with us for hundreds of years and they are playing an increasingly greater role in estate planning. Trusts are most commonly used to distribute property to family members and others under either a will or an inter vivos agreement. The trust developed through the interaction of England’s two parallel legal systems, being the common law and equity. Its origin lies in the concept of the “use”, which was simply a transfer of property by A to B, who was bound by conscience to hold the property for the use of C. While the common law did not recognize C’s rights under such a transfer, the courts of equity would intervene to enforce the moral obligations associated with the use. Thus, the trust was developed by the courts of equity to overcome the inflexibility and harshness of the common law.

Essentially, a trust is an equitable obligation binding one person (the trustee) to deal with property over which he or she has control (the trust property) for the benefit of one or more other persons (the beneficiary or beneficiaries). The trust arises when the owner of the trust property (the settlor, in the case of an inter vivos trust, or the testator, in the case of a trust created by a will) transfers the property to the trustee on specified terms (the trusts), which the trustee accepts. The trustee may also be a beneficiary and any one of the beneficiaries may enforce the obligation. In law, a trust is not a separate legal entity (as a corporation is), except for specific purposes such as income tax. Rather, it is a relationship where one party holds and administers property for the benefit of others.

3. CHARACTERISTICS OF A TRUST

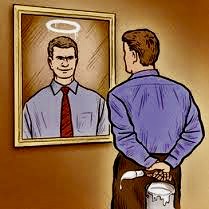

The most important characteristic of a trust is that it is a fiduciary relationship (i.e. a relationship based on confidence or trust). The fiduciary relationship exists between the trustee, who holds title to and administers the trust property, and the beneficiaries, for whose benefit the trust property is held. As a fiduciary, the trustee is subject to onerous obligations, including the obligation to act only in the best interests of the beneficiaries.

Another distinguishing characteristic of a trust is the dual nature of the ownership of the trust property as between the trustee and the beneficiaries. That is, while the trustee has the legal ownership of the property (i.e. the title and legal control), the beneficiaries are entitled to the beneficial ownership of the property (i.e. the rights to use and enjoyment).

4. REQUIREMENTS FOR A VALID TRUST

Three criteria–commonly called “the three certainties”– must be met in order to establish a valid trust. These are:

1. Certainty of intention: It must be clear that the settlor intended that the property transferred to the trustee be held in trust, as a binding obligation. The language used by the alleged settlor must be imperative and not merely an expression of wishes.

2. Certainty of subject-matter: This “certainty” has two aspects. First, it must be possible to identify clearly the property which is to be subject to the trust. Secondly, it must also be possible to define clearly the interests in the trust property to which the beneficiaries are entitled.

3. Certainty of objects: The objects of the trust–that is, the beneficiaries or the purposes for which the trust property is held–must be clearly identified. The word “objects” is a neutral word since a trust may be created either to benefit individuals or to further a particular purpose (e.g. to support cancer research). In each case, however, the objects of the trust must be defined clearly enough that the trust can be carried out.

All three certainties must be present or the trust will fail.

5. TRUSTS AND ESTATE PLANNING

Estate planning is the process whereby an individual identifies and implements steps to achieve the following:

1. the individual’s personal and family objectives for the control and enjoyment of his or her property during his or her lifetime; and

2. the orderly succession to the individual’s property following his or her death.

Estate planning steps may be implemented to take effect either during the individual’s lifetime or following his or her death. In either case, a primary concern will be to achieve the individual’s objectives with as much certainty as possible. Put another way, the goal will be to ensure that the estate plan will be as free as possible from the interference of others, including the courts. While each family and individual is different, in order to achieve estate planning certainty, the estate plan will often involve the use of trusts.

One reason why trusts are used so frequently in estate planning is that they enable an owner of property to give the benefits of the property to others, without having to relinquish ownership or control of the property.

Another reason for the increased use of trusts in estate planning is that there are generally few compliance or reporting requirements, which allows a significant degree of estate planning privacy.

6. DISCRETIONARY TRUSTS

In appropriate circumstances, the discretionary trust may be a particularly effective estate-planning tool. In his text, The Law of Trusts in Canada, Professor Donovan Waters defines a discretionary trust as follows:

A discretionary trust arises when property is vested in trustees and a class of beneficiaries or named persons appear as the trust objects, but the trustees have complete discretion as to the payment of the income, or the capital, or both. The trust may obligate them to distribute all the trust property among the class, but give them a discretion as to whom they make payments within the class, and as to how much they pay to each.

The essence of a discretionary trust is that the trustee cannot be compelled to pay anything to a beneficiary–that any payment of either income or capital, is completely within the discretion of the trustee. Thus, the beneficiary will have no determinable or vested interest in the assets of the trust.

A discretionary trust may be established during the lifetime of the settlor, or alternatively, through a testamentary disposition made under a will.

7. EXAMPLES OF THE USE OF DISCRETIONARY TRUSTS

The flexibility of the discretionary trust as an estate-planning tool is illustrated in the following estate planning situations.

1. Supplementing Government Disability Benefits

A common use of discretionary trusts in estate planning is to provide additional benefits to a disabled person who is receiving government benefits (e.g. a guaranteed annual income) without disentitling the person to the government benefits. Careful planning is often required to avoid the reduction or cancellation of such benefits. In British Columbia, for example, if a disabled person receives an outright inheritance, the amount inherited is deducted dollar-for-dollar from the amount of the government benefits.

Since a discretionary trust gives the trustee an absolute discretion as to whether or not to pay any income or capital to the beneficiary, it can be successfully argued that the beneficiary does not have an equitable interest in the trust. Accordingly, there are certain payments that can be made for a disabled person that will not disentitle him or her to government benefits. Such payments may include medical costs, certain caregiver costs, home repairs and renovations, educational costs and the like. It may also be possible for the trust to purchase capital assets such as a house or vehicle for the use of the beneficiary, without the beneficiary losing entitlement to benefits.

2. Avoiding Wills Variation Challenges

For many British Columbia residents, estate planning must involve a careful consideration of the potential impact of the Wills Variation Act. However, since the Act contains no anti-avoidance provisions, an individual is free to arrange his or her affairs so as to avoid its provisions.

For example, an individual may concerned about a substance-addicted or spendthrift child or spouse challenging his or her will. The individual might use a discretionary trust to provide adequately for the addicted or spendthrift beneficiary, so that any challenge brought by that beneficiary under the Wills Variation Act might fail. The trustee, in his or her discretion, could provide for the beneficiary so that he or she is adequately maintained, but not able to have access to the capital and spend it unwisely.

Furthermore, the Wills Variation Act applies only to those assets that form part of a testator’s estate. If an inter vivos trust is established by a settlor prior to his or her death, and assets are transferred by the settlor to the trustee before the settlor’s death, those assets will not form part of the settlor’s estate. Since the assets are not part of the estate, those assets will not be subject to claims under the Wills Variation Act.

3. Protecting Assets

Almost every individual who undertakes to plan his or her estate will seek a plan that protects his or her assets from the claims of general creditors. In appropriate situations, a discretionary trust may be used to achieve that objective.

If an individual establishes a trust primarily for the purpose of protecting his or her assets from the claims of his or her creditors, and if the individual voluntarily transfers of assets to the trust without consideration, then the trust may be voidable under the Fraudulent Conveyances Act.

On the other hand, if the primary reason for creating the trust is estate planning, then achieving protection against the claims of creditors is simply an ancillary benefit flowing from the creation of the trust. Since the primary purpose for its creation is not to avoid creditors, then the trust should be valid and enforceable. The principal goal is to remove assets from the individual’s estate, before creditor problems arise, so that the assets cannot be attacked by creditors that the individual may subsquently acquire. If placed in a discretionary trust, the assets may be used for the benefit of the individual’s family but may also be protected from the individual’s creditors.

4. Avoiding Claims of Spouses Under the Family Relations Act

With careful drafting, a discretionary trust can be a valuable estate planning tool to enable an individual to enjoy the beneficial use of and interest in property while at the same time protecting the property from claims of his or her spouse under the Family Relations Act.

Consider, for example, an individual who is embarking on a second marriage and wishes to shelter certain property from potential claims of his or her intended spouse under the Family Relations Act. The individual could transfer the property to an irrevocable inter vivos trust under which the individual and his or her children from a previous marriage would constitute the class of beneficiaries. The trust could provide for a discretionary distribution of income and capital during the individual’s lifetime and for an equal distribution of the remaining trust property to the children on the individual’s death. The existence of the trust should effectively prevent the trust property from any subsequent claim by the new spouse under the Family Relations Act.

8. CONCLUSION

The discretionary trust is a powerful and flexible legal tool that can be used for estate planning in many different situations and .for many different purposes. Discretionary trusts are increasingly being used to address unique needs and to achieve specific goals that require a flexible vehicle to suit personal estate planning objectives.