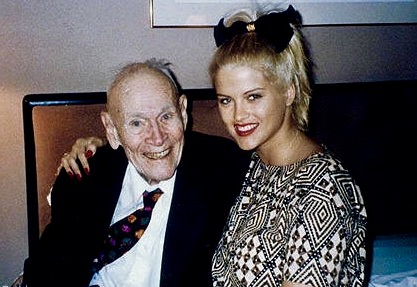

Probably every experienced estate litigation lawyer has had court actions involving a predatory spouse. The phenomenon is disturbing and increasingly common in our society as individuals both live longer and accumulate more wealth.

In simple terms, predatory spouses take advantage of elderly victims and assume control of their financial affairs and often culminate in a secret marriage. The consequences for the victim and their immediate family are traumatic and significant.

Predatory marriage refers to a marriage ceremony entered into for the singular purpose of exploitation, personal gain and profit. Love and personal commitment are simply not part of the equation. The relationship typically begins when a caregiver persuades a vulnerable person to marry. The victim is usually elderly, dependent, vulnerable and suffering from significant cognitive impairment.

The marriage ceremony is usually secretive and the victim is thereafter closeted away from their loved ones as the predator takes control and management of the victim’s financial affairs.

Historically, the courts took an overly simplistic approach to marriage in that they equated marriage to a simple contract requiring minimal mental capacity. In other words, “any idiot can get married”.

Ironically, perhaps, if the contract to enter marriage is so simple, then why does a significant percentage of the legal profession engage in full-time work trying to extricate the parties from the supposedly simple contract?

The Law

One of the early leading cases is from 1885. Durham v. Durham 10 P.D. 80 provided a quote that has been frequently adopted by Canadian courts: “the contract of marriage is a simple one, which does not require a high degree of intelligence to comprehend”.

It is only in recent years that the courts have taken a more realistic approach to the level of mental capacity required to enter into a valid marriage. The law may still be described as being in a state of flux, and the courts typically still view the capacity to marry as a lower threshold than the capacity to manage one’s affairs, make a will, or instruct counsel.

The leading case in British Columbia is Wolfman–Stotland v. Stotland 2011 BCCA 175, which set out the hierarchy of capacity required for various decisions, holding that:

- separation is the simplest act, requiring the lowest level of understanding;

- divorce, while still simple, requires a bit more understanding in that it requires the desire to remain separated and no longer be married;

- American courts have recognized that the mental capacity required for divorce is the same as that required for entering into marriage;

- financial matters require a higher level of understanding than marriage;

- the capacity to instruct counsel involves the ability to understand financial and legal issues, which puts it significantly higher on the competency hierarchy;

- the highest level of capacity is that required to make a will.

A lack of mental capacity to marry will render a marriage void ab initio (as if it had never occurred) per Ross-Scott v. Potvin 2014 BCSC 435.

The law presumes that an adult has capacity unless the contrary is established. The onus of proof for establishing lack of mental capacity to marry is on the person asserting the same.

3 Recent Cases Involving Predatory Spouses

1. Juzumas v. Baron 2012 ONSC 7220

This case involved a predatory marriage where the victim, Mr. Juzumas, was an 88-year-old vulnerable male who was mentally incompetent. The court set aside a wedding and a transfer of his property to the predator’s son on the basis of the doctrines of undue influence and unconscionability.

Ms. Baron, the predator spouse, was a 64-year-old widow who had been married previously 6 to 8 times and had a history of caring for older men with the expectation of receiving an inheritance through their estates. She befriended Mr. Juzumas and promised to live together and care for him. He married her and signed a will naming her as the executrix and sole beneficiary.

After the marriage ceremony Ms. Baron continued to live in a separate apartment with her 23-year-old son and only visited her purported husband for several hours a week. She became increasingly abusive controlling and domineering towards Mr. Juzumas.

Without her knowledge, Mr. Juzumas ultimately changed his will to leave Ms. Baron only a modest bequest of $10,000. When she found out she embarked on a campaign to ensure that she received Mr. Juzumas s’s home. Through the assistance of a lawyer, an agreement was drafted that transferred the property to Ms. Baron’s son and Mr. Juzumas was left with a life interest in his home.

At the time of the transfer, Mr. Juzumas was 91 years of age, vulnerable, in failing health and completely dependent on and dominated by his abusive spouse. He lived in constant fear of being abandoned to a nursing home, with which Ms. Walker continually threatened him.

He commenced a court action to set aside the transfer of the property and sought a divorce and dissolution of the marriage.

The court set aside the transfer of land on the basis of the doctrines of undue influence and unconscionability, both of which may be used “where a stronger party takes advantage of a weaker party in the course of inducing the weaker party’s consent to an agreement”.

The court found that there was actual undue influence by reason of the fact that Ms. Baron threatened an elderly dependent with abandonment to a care home.

The court also found presumptive undue influence by reason of the fact that she was a caregiver who had the ability or potential to dominate the will of the other, whether through manipulation, coercion, or outright but subtle abuse of power.

It was incumbent upon the wife to rebut the presumption of undue influence and demonstrate that the transaction was an exercise of independent free will, which she was completely unable to do.

The court also relied upon the doctrine of unconscionability which gives the court the jurisdiction to set aside an agreement resulting from an inequality of bargaining power. The onus is on the defendant to establish the fairness of the transaction.

2. Hunt v. Worrod 2017 ONSC 7397

The facts of this case are perhaps as egregious as they possibly may be with respect to predatory marriages.

As a result of a catastrophic head injury, the 50-year-old Mr. Hunt had been in a coma for 18 days and hospitalized for four months. The injury left him with what doctors described as a wasted, shrunken brain.

Three days after leaving hospital, Mr. Hunt was spirited away by the defendant Worrod, a former girlfriend, for a secret wedding that gave her legal rights to his future wealth and his landscaping business, home and expected $1 million personal injury settlement.

Mr. Hunt’s concerned children contacted the police, who located him in a motel just hours after the purported wedding took place. His sons had been made his legal guardians by court order.

Mr. Hunt never lived with his purported wife after the marriage. Before the accident he had had an on-again, off-again relationship with Ms. Worrod and had concluded their relationship with a separation agreement that resolved all of their property and legal obligations to each other. In fact, he had been required to contact the police to remove her from his residence when the relationship ended.

It was noted that Ms. Worrod was an extreme alcoholic who had hit Mr. Hunt when drunk and was generally unable to act and care responsibly for herself while intoxicated.

Evidence at trial from various medical experts was conclusive that Mr. Hunt was intellectually devastated with serious physical and cognitive issues that made him increasingly malleable and easily influenced through emotional stimulation, including sexual relations.

The medical evidence was consistent that Mr. Hunt suffered a classic case of frontal lobe syndrome that limited his ability to reason abstractly, problem solve, make decisions or consider alternatives, and that he lacked insight and self-awareness. His cognitive limitations severely limited his ability to understand the consequences of his behaviors and actions.

All of the various medical experts who testified made it clear that Mr. Hunt did not have the capacity to marry. As stated in Ross-Scott v. Potvin 2014 BCSC 435:

“A person is capable of entering into a marriage contract only if he or she has the capacity to understand the nature of the contract and duties and responsibilities it creates. The assessment of a person’s capacity to understand the nature of the marriage commitment is informed, in part, by an ability to manage themselves and their affairs. Delusional thinking or reduced cognitive abilities alone may not destroy an individual’s capacity to form an intention to marry as long as the person is capable of managing their own affairs.”

The court concluded that Mr. Hunt did not have the requisite capacity to marry as he did not understand the nature of the contract he was entering into and the responsibilities the contract created.

The marriage was declared void ab initio and Ms. Worrod was ordered to have no further contact with Mr. Hunt.

3. Devore-Thompson v Poulain 2017 BCSC 1289

The deceased, Donna Walker, suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and in September 2010 was declared by the court to be incapable of managing her financial and legal affairs because of her dementia. She had moved into a care facility in September 2010, where she remained until her death in late 2013 at age 74.

Ms. Walker had purportedly married the defendant Poulain in June 2010 but they never lived together, either before or after the marriage ceremony.

The overwhelming evidence of several lay witnesses, as well as a treating geriatric psychiatrist, was that Ms. Walker had lacked mental capacity to marry in 2010.

For example, one lay witness testified that Ms. Walker had told her that she did not know where she was married, who married her, or even why she married the defendant. Once again, the marriage was done in secret and there were no friends or family at the wedding service.

There was one photograph taken at the wedding ceremony which clearly indicated that Ms. Walker’s facial expression was vacant.

After her first marriage ended, Ms. Walker had always told those close to her that she never wished to marry again. She was very close to her family and friends but never expressed to a single witness that she was in love with the defendant, that she knew anything about him, that they had any kind of future together, or that she wanted to get married and spend the rest of her life with him.

The evidence of the treating geriatric psychiatrist was most significant, in that she testified as follows:

- Ms. Walker did not understand reality, absorb information or make decisions based on the correct facts, and that she had no insight or judgment.

- On learning of the purported marriage, the psychiatrist had made an urgent referral to the Public Guardian and Trustee stating that Ms. Walker was incapable of entering into a marriage relationship as she was moderately to severely demented and had significant impairment of executive function. She also noted that Ms. Walker was at significant risk for abuse as a vulnerable adult.

- Ms. Walker did not have a grip on reality but insisted that she was fully independent for self-care and household management, despite much evidence to the contrary.

The defendant testified that he had no concern about Ms. Walker’s mental capacity.

The court had no difficulty in finding the defendant to be a completely untruthful witness who was motivated by a desire for financial gain from Ms. Walker’s assets.

The court concluded that Ms. Walker’s mental capacity had diminished to such an extent that she could not have formed an intention to live with the defendant or to form a lifetime bond. At the time of the marriage she did not understand what it meant to live together with another person, and could not know even the most basic meaning of marriage or understand any of its implications, including who she was married to, in the sense of what kind of person he was, what their emotional attachment was, that they would be living together, and fundamentally how marriage would affect her life on a day-to-day basis in the future.

Accordingly, the court found that Ms. Walker did not have the capacity to marry the defendant and the marriage was declared void ab initio. Two wills done by Ms. Walker in 2007 and 2009 were also set aside by reason of her lack of capacity.

Conclusion

The advent of a rapidly aging population with significant wealth will certainly lead to a rise in the increasingly common phenomenon of predatory marriage.

The legal issue of mental capacity to enter into such a marriage will increasingly become more relevant and litigated.

The legal test for capacity to marry is in a state of flux. It will undoubtedly continue to evolve as more instances of predatory marriage are brought before the courts and they become more accustomed to recognizing such predatory behavior.

To some extent I believe it is a situation where the courts need to be more cognizant of the significant number of predators in our society who prey upon the infirm and vulnerable.

The concept that only a low level of mental capacity is required to enter into a marriage is an anachronism that needs to be corrected, given the complexity of current family law, particularly as it relates to property entitlement to the assets of one spouse.

At present, to succeed in having a purported predatory marriage set aside, it is necessary to prove on the balance of probabilities that the victim lacked mental capacity to understand the nature of the marital contract, which typically requires both the testimony of lay witnesses and medical evidence of lack of capacity.

The Juzumas v. Baron decision is significant in that the court also invoked the doctrines of undue influence and unconscionability in setting aside the purported marriage. Hopefully it will be followed by other court decisions as useful tools to remedy a wrong suffered in the context of a predatory marriage and financial abuse.